Sir

Francis Drake 1590

Sir

Francis Drake (c. 1540 – 28 January 1596) was a privateer, know by the Spanish as,

El Draque, a Sea Dogs, and branded a

pirate.

He

was an English sea captain, naval officer, slave trader and explorer. Drake is most famously known for his

circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition, from 1577 to 1580, and was the first to complete the voyage as captain while leading the expedition throughout the entire circumnavigation. With his incursion into the

Pacific

Ocean, he claimed what is now California for the English and inaugurated an era of conflict with the Spanish on the western coast of the Americas, an area that had previously been largely unexplored by western shipping.

Elizabeth I awarded Drake a knighthood in 1581 which he received on the Golden Hind in Deptford. In the same year he was appointed mayor of Plymouth. As a vice admiral, he was second-in-command of the English fleet in the victorious battle against the Spanish Armada in 1588. After unsuccessfully attacking San Juan, Puerto Rico, he died of dysentery in January 1596.

Drake's exploits made him a hero to the English, but his privateering led

King Philip II of Spain to (allegedly) offer a reward of 20,000 ducats for his capture or death, about £6 million (US$8 million) in modern currency. Some call Drake a slave trader since as a young man, he served under his cousin

Richard

Hawkins, who led some of the earliest English slaving voyages of the

Elizabethan era.

At

the age of twenty (ca. 1563-1564) he made a voyage to the coast of Guinea in a ship owned by William and John Hawkins, some of his relatives from Plymouth.

In 1566-1567, Drake, made his first voyage to the Americas, sailing under Captain John Lovell on one of a fleet of ships owned by the Hawkins family. They attacked Portuguese towns and ships on the coast of West Africa and then sailed to the Americas and sold the captured cargoes of slaves to Spanish plantations. The voyage was largely unsuccessful and more than 90 slaves were released without payment.

Drake's second voyage to the Americas and his second slaving voyage ended in the ill-fated 1568 incident at San Juan de Ulúa. Whilst negotiating to

re-supply and repair at a Spanish port in Mexico, the fleet was attacked by Spanish warships, with all but two of the English ships lost. He escaped along with John Hawkins, surviving the attack by swimming. Drake's hostility towards the Spanish is said to have started with this incident and Drake vowed revenge.

In 1570, his reputation enabled him to proceed to the West Indies with two vessels under his command. He renewed his visit the next year for the sole purpose of obtaining information.

DRAKE'S FIRST VICTORY

In 1572, he embarked on his first major independent enterprise. He planned an attack on the Isthmus of Panama, known to the Spanish as Tierra Firme and the English as the Spanish Main. This was the point at which the silver and gold treasure of Peru had to be landed and sent overland to the

Caribbean

Sea, where galleons from Spain would pick it up at the town of Nombre de Dios. Drake left Plymouth on 24 May 1572, with a crew of 73 men in two small vessels, the Pascha (70 tons) and the Swan (25 tons), to capture Nombre de Dios.

His first raid was late in July 1572. Drake formed an alliance with the Cimarrons. Drake and his men captured the town and its treasure. When his men noticed that Drake was bleeding profusely from a wound, they insisted on withdrawing to save his life and left the treasure. Drake stayed in the area for almost a year, raiding Spanish shipping and attempting to capture a treasure shipment.

The most celebrated of Drake's adventures along the Spanish Main was his capture of the Spanish Silver Train at Nombre de Dios in March 1573. He raided the waters around Darien (in modern Panama) with a crew including many French privateers including Guillaume Le Testu, a French buccaneer, and African slaves (Maroons) who had escaped the Spanish. One of these men was Diego, who under Drake became a free man was also a capable ship builder. Drake tracked the Silver Train to the nearby port of Nombre de Dios. After their attack on the richly laden mule train, Drake and his party found that they had captured around 20 tons of silver and gold.

They buried much of the treasure, as it was too much for their party to carry, and made off with a fortune in gold. (An account of this may have given rise to subsequent stories of pirates and

buried

treasure). Wounded, Le Testu was captured and later beheaded. The small band of adventurers dragged as much gold and silver as they could carry back across some 18 miles of jungle-covered mountains to where they had left the raiding boats. When they got to the coast, the boats were gone. Drake and his men, downhearted, exhausted and hungry, had nowhere to go and the Spanish were not far behind.

At this point, Drake rallied his men, buried the treasure on the beach, and built a raft to sail with two volunteers ten miles along the surf-lashed coast to where they had left the flagship. When Drake finally reached its deck, his men were alarmed at his bedraggled appearance. Fearing the worst, they asked him how the raid had gone. Drake could not resist a joke and teased them by looking downhearted. Then he laughed, pulled a necklace of Spanish gold from around his neck and said "Our voyage is made, lads!" By 9 August 1573, he had returned to Plymouth.

It was during this expedition that he climbed a high tree in the central mountains of the Isthmus of Panama and thus became the first Englishman to see the

Pacific

Ocean. He remarked as he saw it that he hoped one day an Englishman would be able to sail it – which he would do years later as part of his circumnavigation of the world.

When Drake returned to Plymouth after the raids, the government signed a temporary truce with King Philip II of Spain and so was unable to acknowledge Drake's accomplishment officially. Drake was considered a hero in England and a pirate in Spain for his raids.

CIRCUMNAVIGATION 1577-1580

With the success of the Panama isthmus raid in 1577, Elizabeth I of England sent Drake to start an expedition against the Spanish along the Pacific coast of the Americas. Drake used the plans that Sir Richard Grenville had received the patent for in 1574 from Elizabeth, which was rescinded a year later after protests from Philip of Spain. Diego was once again employed under Drake; his fluency in Spanish and English would make him a useful interpreter when Spaniards or Spanish-speaking Portuguese were captured. He was employed as Drake's servant and was paid wages, just like the rest of the crew. Drake and the fleet set out from Plymouth on 15 November 1577, but bad weather threatened him and his fleet. They were forced to take refuge in Falmouth, Cornwall, from where they returned to Plymouth for repair.

After this major setback, Drake set sail again on 13 December aboard Pelican with four other ships and 164 men. He soon added a sixth ship, Mary (formerly Santa Maria), a Portuguese merchant ship that had been captured off the coast of Africa near the Cape Verde Islands. He also added its captain, Nuno da Silva, a man with considerable experience navigating in South American waters.

Drake's fleet suffered great attrition; he scuttled both Christopher and the flyboat Swan due to loss of men on the

Atlantic crossing. He made landfall at the gloomy bay of San Julian, in what is now Argentina. Ferdinand Magellan had called here half a century earlier, where he put to death some mutineers. Drake's men saw weathered and bleached skeletons on the grim Spanish gibbets. Following Magellan's example, Drake tried and executed his own "mutineer" Thomas Doughty. The crew discovered that Mary had rotting timbers, so they burned the ship. Drake decided to remain the winter in San Julian before attempting the Strait of Magellan.

THE PACIFIC 1578

The three remaining ships of his convoy departed for the Magellan Strait at the southern tip of South America. A few weeks later (September 1578) Drake made it to the Pacific, but violent storms destroyed one of the three ships, the Marigold (captained by John Thomas) in the strait and caused another, the Elizabeth captained by John Wynter, to return to England, leaving only the Pelican. After this passage, the Pelican was pushed south and discovered an island that Drake called Elizabeth Island. Drake, like navigators before him, probably reached a latitude of 55°S (according to astronomical data quoted in Hakluyt's The Principall Navigations, Voiages and Discoveries of the English Nation of 1589) along the Chilean coast. In the Magellan Strait Francis and his men engaged in skirmish with local indigenous people, becoming the first Europeans to kill indigenous peoples in southern Patagonia. During the stay in the strait, crew members discovered that an infusion made of the bark of Drimys winteri could be used as remedy against scurvy. Captain Wynter ordered the collection of great amounts of bark – hence the scientific name.

Despite popular lore, it seems unlikely that Drake reached Cape Horn or the eponymous Drake Passage, because his descriptions do not fit the first and his shipmates denied having seen an open sea. Historian Mateo Martinic, who examined his travels, credits Drake with the discovery of the "southern end of the Americas and the oceanic space south of it". The first report of his discovery of an open channel south of Tierra del Fuego was written after the 1618 publication of the voyage of Willem Schouten and Jacob le Maire around Cape Horn in 1616.

Drake pushed onwards in his lone flagship, now renamed the Golden Hind in honour of Sir Christopher Hatton (after his coat of arms). The Golden Hind sailed north along the Pacific coast of South America, attacking Spanish ports and pillaging towns. Some Spanish ships were captured, and Drake used their more accurate charts. Before reaching the coast of Peru, Drake visited Mocha Island, where he was seriously injured by hostile Mapuche. Later he sacked the port of Valparaíso further north in Chile, where he also captured a ship full of Chilean wine.

SPANISH TREASURE SHIPS

Near Lima, Drake captured a Spanish ship laden with 25,000 pesos of Peruvian gold, amounting in value to 37,000 ducats of Spanish money (about £7m by modern standards). Drake also discovered news of another ship, Nuestra Señora de la Concepción, which was sailing west towards Manila. It would come to be called the Cacafuego. Drake gave chase and eventually captured the treasure ship, which proved his most profitable capture.

Aboard Nuestra Señora de la Concepción, Drake found 36 kilograms (80 lb) of gold, a golden crucifix, jewels, 13 chests full of royals of

plate and 26 thousand kilograms (26 long tons) of silver. Drake was naturally pleased at his good luck in capturing the galleon, and he showed it by dining with the captured ship's officers and gentleman passengers. He offloaded his captives a short time later, and gave each one gifts appropriate to their rank, as well as a letter of safe conduct.

CALIFORNIAN COAST: NOVA ALBION 1579

Prior to Drake's voyage, the western coast of North America had only been partially explored in 1542 by Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo who sailed for Spain. So, intending to avoid further conflict with Spain, Drake navigated northwest of Spanish presence and sought a discreet site at which the crew could prepare for the journey back to England.

On 5 June 1579, the ship briefly made first landfall at South Cove, Cape Arago, just south of Coos Bay, Oregon, and then sailed south while searching for a suitable harbour to repair his ailing ship. On 17 June, Drake and his crew found a protected cove when they landed on the Pacific coast of what is now Northern California. While ashore, he claimed the area for Queen Elizabeth I as Nova Albion or New Albion. To document and assert his claim, Drake posted an engraved plate of brass to claim sovereignty for Elizabeth and every successive English monarch. After erecting a fort and tents ashore, the crew labored for several weeks as they prepared for the circumnavigating voyage ahead by careening their ship, Golden Hind, so to effectively clean and repair the hull. Drake had friendly interactions with the Coast Miwok and explored the surrounding land by foot. When his ship was ready for the return voyage, Drake and the crew left New Albion on 23 July and paused his journey the next day when anchoring his ship at the Farallon Islands where the crew hunted seal meat.

PACIFIC AND AROUND AFRICA

Drake left the Pacific coast, heading southwest to catch the winds that would carry his ship across the Pacific, and a few months later reached the Moluccas, a group of islands in the western Pacific, in eastern modern-day Indonesia. At this time Diego died from wounds he had sustained earlier in the voyage, Drake was saddened at his death having become a good friend. Golden Hind later became caught on a reef and was almost lost. After the sailors waited three days for convenient tides and had dumped cargo. Befriending Sultan Babullah of Ternate in the Moluccas, Drake and his men became involved in some intrigues with the Portuguese there. He made multiple stops on his way toward the tip of Africa, eventually rounded the Cape of Good Hope, and reached Sierra Leone by 22 July 1580.

RETURN TO PLYMOUTH 1580

On 26 September, Golden Hind sailed into Plymouth with Drake and 59 remaining crew aboard, along with a rich cargo of spices and captured Spanish treasures. The Queen's half-share of the cargo surpassed the rest of the crown's income for that entire year. Drake was hailed as the first Englishman to circumnavigate the Earth (and the second such voyage arriving with at least one ship intact, after Elcano's in 1520).

The Queen declared that all written accounts of Drake's voyages were to become the Queen's secrets of the Realm, and Drake and the other participants of his voyages on the pain of death sworn to their secrecy; she intended to keep Drake's activities away from the eyes of rival Spain. Drake presented the Queen with a jewel token commemorating the

circumnavigation. Taken as a prize off the Pacific coast of Mexico, it was made of enamelled gold and bore an African diamond and a ship with an ebony hull.

For her part, the Queen gave Drake a jewel with her portrait, an unusual gift to bestow upon a commoner, and one that Drake sported proudly in his 1591 portrait by Marcus Gheeraerts now at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich. On one side is a state portrait of Elizabeth by the miniaturist Nicholas Hilliard, on the other a sardonyx cameo of double portrait busts, a regal woman and an African male. The "Drake Jewel", as it is known today, is a rare documented survivor among sixteenth-century jewels; it is conserved at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

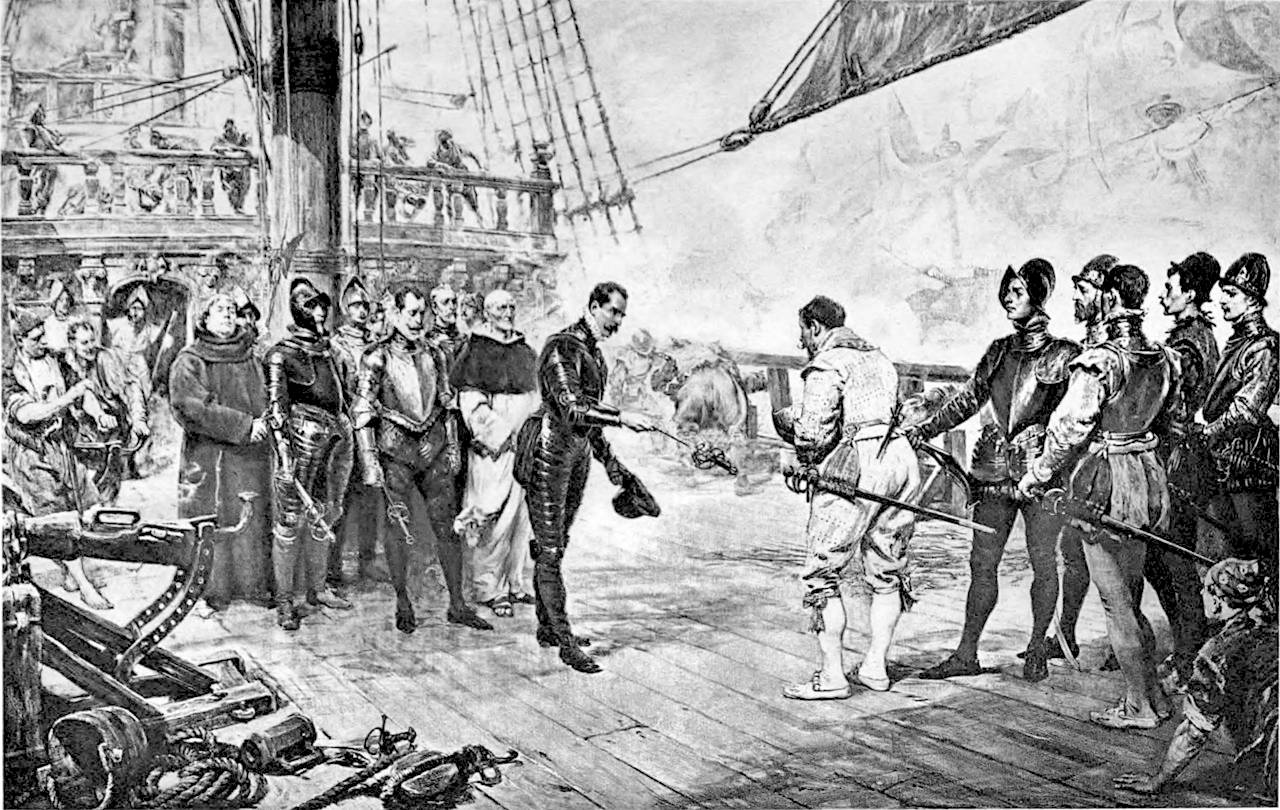

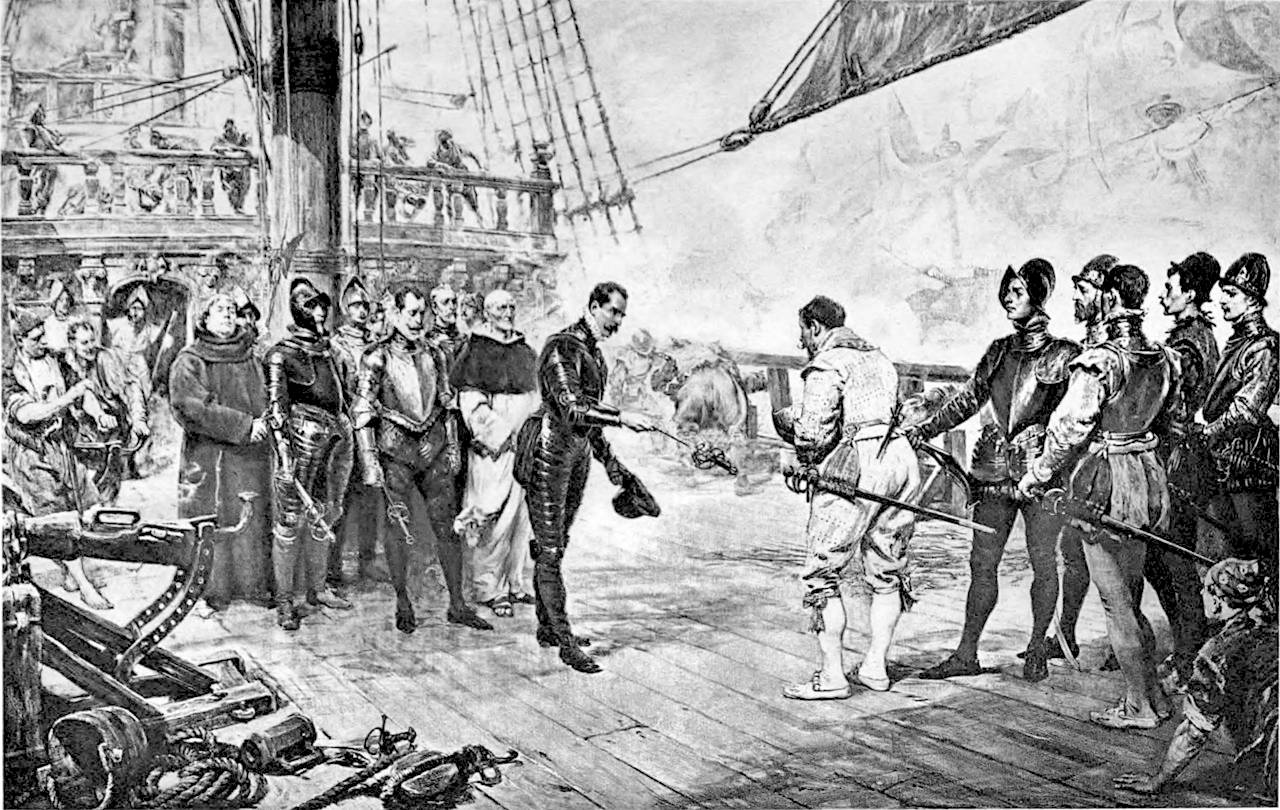

KNIGHTHOOD

Queen Elizabeth awarded Drake a knighthood aboard Golden Hind in Deptford on 4 April 1581; the dubbing being performed by a French diplomat, Monsieur de Marchaumont, who was negotiating for Elizabeth to marry the King of France's brother, Francis, Duke of Anjou. By getting the French diplomat involved in the knighting, Elizabeth was gaining the implicit political support of the French for Drake's actions. During the Victorian era, in a spirit of nationalism, the story was promoted that Elizabeth I had done the knighting.

After receiving his knighthood Drake unilaterally adopted the armorials of the ancient Devon family of Drake of Ash, near Musbury, to whom he claimed a distant but unspecified kinship. These arms were: Argent, a wyvern wings displayed and tail nowed gules, and the crest, a dexter arm Proper grasping a battle axe Sable, headed Argent. The head of that family, also a distinguished sailor, Sir Bernard Drake (d.1586), angrily refuted Sir Francis's claimed kinship and his right to bear his family's arms. That dispute led to "a box on the ear" being given to Sir Francis by Sir Bernard at court, as recorded by John Prince (1643–1723) in his "Worthies of Devon", first published in 1701. Queen Elizabeth, to assuage matters, awarded Sir Francis his own coat of arms, blazoned as follows:

Sable a fess wavy between two pole-stars [Arctic and Antarctic] argent; and for his crest, a ship on a globe under ruff, held by a cable with a hand out of the clouds; over it this motto, Auxilio Divino; underneath, Sic Parvis Magna; in the rigging whereof is hung up by the heels a wivern, gules, which was the arms of Sir Bernard Drake.

The motto, Sic Parvis Magna, translated literally, is:

"Thus great things from small things

(come)"

The hand out of the clouds, labelled Auxilio Divino, means:

"With Divine

Help"

GREAT AMERICAN EXPEDITION

War had already been declared by Phillip II after the Treaty of Nonsuch, so the Queen through Francis Walsingham ordered Sir Francis Drake to lead an expedition to attack the Spanish colonies in a kind of preemptive strike. An expedition left Plymouth in September 1585 with Drake in command of twenty-one ships with 1,800 soldiers under Christopher Carleill. He first attacked Vigo in Spain and held the place for two weeks ransoming supplies. He then plundered Santiago in the Cape Verde islands after which the fleet then sailed across the Atlantic, sacked the port of Santo Domingo, and captured the city of Cartagena de Indias in present-day Colombia. At Cartagena, Drake released one hundred Turks held as slaves. On 6 June 1586, during the return leg of the voyage, he raided the Spanish fort of San Agustín in Spanish Florida.

After the raids he then went on to find Sir Walter Raleigh's settlement much further north at Roanoke which he replenished and also took back with him all of the original colonists before Sir Richard Greynvile arrived with supplies and more colonists. He finally reached England on 22 July, when he sailed into Portsmouth, England to a hero's welcome.

THE SPANISH ARMADA

Angered by these acts, Philip II ordered a planned invasion of England.

Cádiz raid

On 15 March 1587, Drake accepted a new commission with several purposes: disrupt the shipping routes to slow supplies from Italy and Andalucia to Lisbon, to trouble enemy fleets that were in their own ports, and to capture Spanish ships laden with treasure. Drake was also to confront and attack the Spanish Armada had it already sailed for England. When arriving at Cadiz on 19 April, Drake found the harbour packed with ships and supplies as the Armada was readying and waiting for fair wind to launch the fleet to attack. In the early hours of the next day, Drake pressed his attack into the inner harbour and inflicted heavy damage. Claims of the Spanish ship losses vary. Drake claimed he had sunk 39 ships, but other contemporary sources are lower, specifically some Spanish sources which suggest losses as low as 25 ships. The attack became known as the “singeing of the King’s beard” and delayed the Spanish invasion by a year.

Over the next month, Drake patrolled the Iberian coasts between Lisbon and Cape St. Vincent, intercepting and destroying ships on the Spanish supply lines. Drake estimated that he captured around 1600–1700 tons of barrel staves, enough to make 25,000 to 30,000 barrels (4,800 m3) for containing provisions.

Defeat of the Spanish Armada

Drake was vice admiral in command of the English fleet (under Lord Howard of Effingham) when it overcame the Spanish Armada that was attempting to invade England in 1588. As the English fleet pursued the Armada up the English Channel in closing darkness, Drake broke off and captured the Spanish galleon Nuestra Señora del Rosario, along with Admiral Pedro de Valdés and all his crew. The Spanish ship was known to be carrying substantial funds to pay the Spanish Army in the Low Countries. Drake's ship had been leading the English pursuit of the Armada by means of a lantern. By extinguishing this for the capture, Drake put the fleet into disarray overnight.

On the night of 29 July, along with Howard, Drake organised fire-ships, causing the majority of the Spanish captains to break formation and sail out of Calais into the open sea. The next day, Drake was present at the Battle of Gravelines. He wrote as follows to Admiral Henry Seymour after coming upon part of the Spanish Armada, whilst aboard Revenge on 31 July 1588 (21 July 1588 OS):

Coming up to them, there has passed some common shot between some of our fleet and some of them; and as far as we perceive, they are determined to sell their lives with blows.

The most famous (but probably apocryphal) anecdote about Drake relates that, prior to the battle, he was playing a game of bowls on Plymouth Hoe. On being warned of the approach of the Spanish fleet, Drake is said to have remarked that there was plenty of time to finish the game and still beat the Spaniards, perhaps because he was waiting for high tide.

There is no known eyewitness account of this incident and the earliest retelling of it was printed 37 years later. Adverse winds and currents caused some delay in the launching of the English fleet as the Spanish drew nearer, perhaps prompting a popular myth of Drake's cavalier attitude to the Spanish threat. It might also have been later ascribed to the stoic attribute of British culture.

Please use our

A-Z INDEX to

navigate this site