|

THE TRADE WINDS

Please use our A-Z INDEX to navigate this site or return HOME

|

|

PlanetSolar heading out into uncharted technical waters. The theory was in place, but nobody knew if this solar powered boat could make it. But they did! The solar panel area on this ship was increased with solar panels on rollers, pulled out by the crew using winches. The Elizabeth Swann uses robotics and hydraulics to move solar wings that automatically track the sun, and fold away in storm conditions. PlanerSolar did not seek to advantage itself of the trade winds, except by the shape of the hull and the rear wing that could be raised for some slight sail (drag) effect.

1. Deciding when to go, 2. Which route to follow and 3. The sails to carry.

The main consideration for leisure sailors is to avoid the hurricane season from June to November. So most yachts leave in late November to arrive in time for Christmas. Although the trade-winds in January are often stronger. Of course you have to know how to sail, trim and tack your boat. It takes a lot of work and constant vigilance.

With a wind turbine, or rotary sail, such considerations are irrelevant.

There

are lessons to be learned from yachties, lost on many ship captains

today, who simply ignore what Christopher Columbus

and Vasco Da Gama

learned the hard way. If only we could take out much of the guesswork.

It is well worth considering such a problem as if we were reliant on

sails.

During a typical crossing, the trade-winds will be Force 4 or 5, with some lighter periods and a few days of winds of 25-plus knots. A flexible sail-plan is necessary to take account of the changing wind strengths – there is no one-size-fits-all answer. The most common sail-plan is goose-winged (sails out on either side of a boat), with most skippers carrying a specialist downwind sail for when the wind goes light.

The main peril of sailing downwind in a breeze is rolling. It may start gently but within seconds you can be rolling from rail to rail and a moment later she rolls too far.

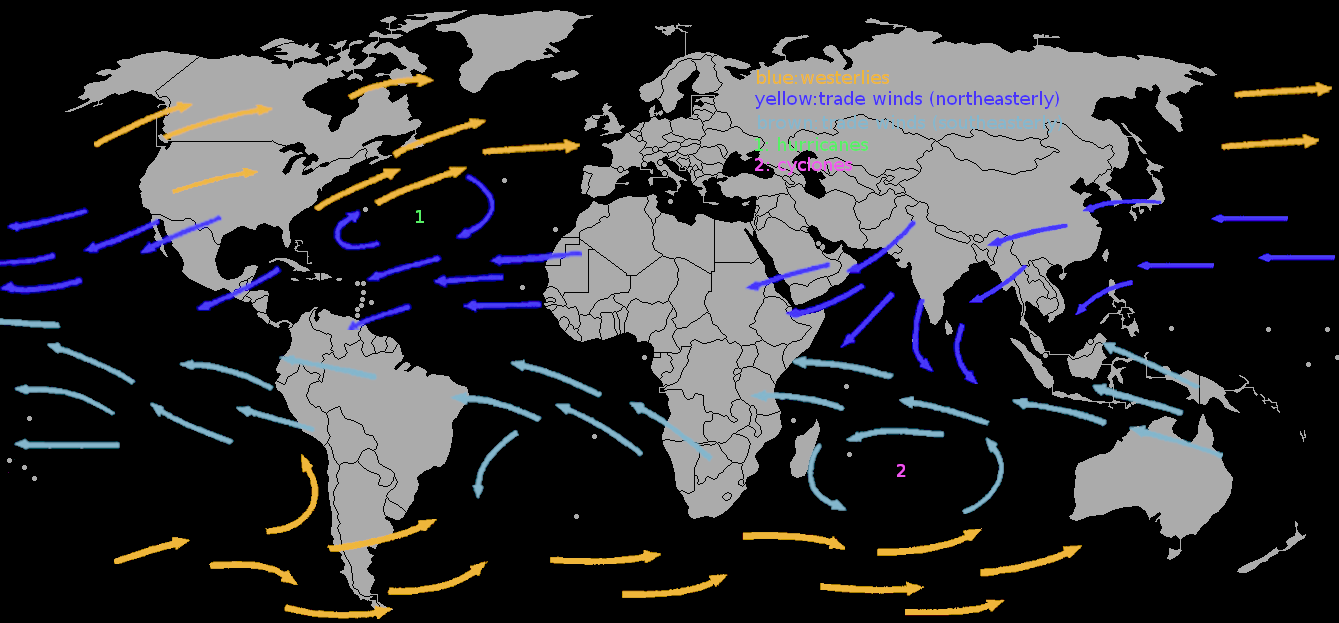

Map of the oceans, showing the trade winds. The global oceanic system has five major sea current gyres that act as large conveyor belts.

The gyres are also correlated with dominant wind flows where they rotate clockwise north of the equator and counterclockwise south of the equator. During the era of sail ship navigation, these gyres had a strong impact on navigators and trade flows.

TRADE WINDS & OCEAN CURRENTS

The trade winds or easterlies are the permanent east-to-west prevailing winds that flow in the Earth's equatorial region (between 30°N and 30°S latitudes). The trade winds blow mainly from the northeast in the Northern Hemisphere and from the southeast in the Southern Hemisphere, strengthening during the winter and when the Arctic oscillation is in its warm phase. Trade winds have been used by captains of sailing ships to cross the world's oceans for centuries and enabled colonial expansion into the Americas and trade routes to become established across the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

In order to make sense of all of these variables, we will need to combine information from the Elizabeth Swann's instruments, feed them into a database and access that data from stored patterns, combined with real time performance readings, to define the best route at any time of year for a solar and wind powered commercial vessel.

Ocean currents sometimes oppose wind direction, where warm water is does not always follow what might be imagined as a logical pattern. Like many processes in the ocean, salinity is tied to weather and circulation. For example, trade winds blow moist air from the Atlantic across Central America and into the Pacific Ocean, which concentrates salinity in the Atlantic waters left behind. As a result, the Atlantic is slightly saltier than the Pacific.

|

|

|

Please use our A-Z INDEX to navigate this site

This website is Copyright © 2020 Jameson Hunter Ltd

|