|

NEW

BOY ON THE BLOCK - In this CAD end elevation, it is possible to see how the simple trimaran hull design lends itself

to experimental use of methanol in the quest for zero emission waterborne

transport. But like

all technical challenges, until somebody does it, the trophy remains up for

grabs. Nobody has yet crossed the major oceans on methanol as a stored fuel.

One of the biggest challenges from the perspective of maritime decarbonisation is that most methanol today is produced using natural gas (grey methanol) or coal (brown

methanol), thus is not sustainable.

Methanol

is a biodegradable alcohol that can be used in internal

combustion engines, typically with diesel, or in fuel cells, for an

all electric propulsion solution. But how might this be achieved and

what range and performance might we expect, and finally what is the

cost?

The

design of the Elizabeth Swann's hulls gives us the opportunity to

incorporate substantial methanol storage tanks for use in fuel

cells, if and as appropriate - or even

as a demonstrator for various marine electric systems.

We

are looking for a good compromise, reduced weight, at a sensible price,

while still offering the storage capacity for blue water voyages and for

use as a medium size ferry.

Methanol

is more readily deliverable and thus available at ports. For this

reason, and although we are open to testing other systems, the economics

at present favour CH3OH. At time of writing in March 2022, we don't yet

have a methanol partner.

INTERNAL

COMBUSTION ENGINES

Methanol is mixed with water and injected into high performance diesel and gasoline engines for an increase of power and a decrease in intake air temperature in a process known as

water methanol injection.

The chief advantage of a methanol economy is that it could be adapted to

gasoline internal combustion engines with minimum modification to the engines and to the infrastructure that delivers and stores liquid fuel. Its energy density is however only half that of gasoline, meaning that twice the volume of methanol would be required.

Methanol is an alternative fuel for ships that helps the shipping industry meet increasingly strict emissions regulations. It significantly reduces emissions of sulphur oxides (SOx), nitrogen oxides (NOx) and particulate matter. Methanol can be used with high efficiency in marine

diesel engines after minor modifications using a small amount of pilot fuel (Dual fuel).

Methanol, also known as methyl alcohol, amongst other names, is a chemical and the simplest alcohol, with the formula CH3OH (a methyl group linked to a hydroxyl group, often abbreviated MeOH). It is a light, volatile, colourless, flammable liquid with a distinctive alcoholic odour similar to that of ethanol (potable alcohol). A polar solvent, methanol acquired the name wood alcohol because it was once produced chiefly by the destructive distillation of wood. Today, methanol is mainly produced industrially by hydrogenation of carbon monoxide.

FILLING

THE TANKS UP

Methanol is a globally available fuel, claimed to be sold in over 100 ports worldwide, and among the lowest emission fuels for marine engines. Methanol is already making an impact in ports and on the high seas, powering tankers, ferries, pilot boats and more.

Methanol has a high energy density (3450 Wh kg and 3000 Wh l in a 1:1 molar ratio with water). It is easy to handle and is completely miscible with

water, but is corrosive to some metals (aluminium). It can also be produced from a variety of sources and is available

from pharmacies at a low price.

The energy density of hydrogen is 520 Wh/L (in case of 2,000 psi gas cylinder). However, methanol has 4,817 Wh/L of energy density Since space and weight are at a premium in most transportation, DMFC is attractive for transportation applications.

GLOBAL

ECONOMY

As the global economy prepares for an energy transition that will change the future of energy landscapes, new alternative fuels are coming to the fore. Hydrogen has been gaining traction as a clean alternative fuel as it only emits water upon combustion. However, there are a number of inherent challenges with the production, handling, and consumption of hydrogen with the state of technology today. It is still expensive to produce clean hydrogen from renewable sources. As a gas, hydrogen also requires capital-intensive infrastructure for its storage and transport.

Methanol is tomorrow’s hydrogen, today. It is an extremely efficient hydrogen carrier, packing more hydrogen in one simple alcohol molecule than can be found in hydrogen. Being a liquid at ambient conditions, methanol can be handled, stored, and transported with ease by leveraging existing infrastructure that supports the global trade of methanol. Methanol reformers are able to generate on-demand hydrogen at the point of use to avoid the complexity and high cost associated with the logistics of hydrogen as a fuel. Methanol can also be produced from sustainable and green pathways to allow it to be a carrier of low carbon, and potentially carbon-neutral, hydrogen.

Fuel cells use hydrogen as a fuel to produce clean and efficient electricity that can power cars, trucks, buses, ships, cell phone towers, homes and businesses. Methanol is an excellent hydrogen carrier fuel, packing more hydrogen in this simple alcohol molecule than can be found in hydrogen that’s been compressed (350-700 bar) or

liquefied (-253˚C).

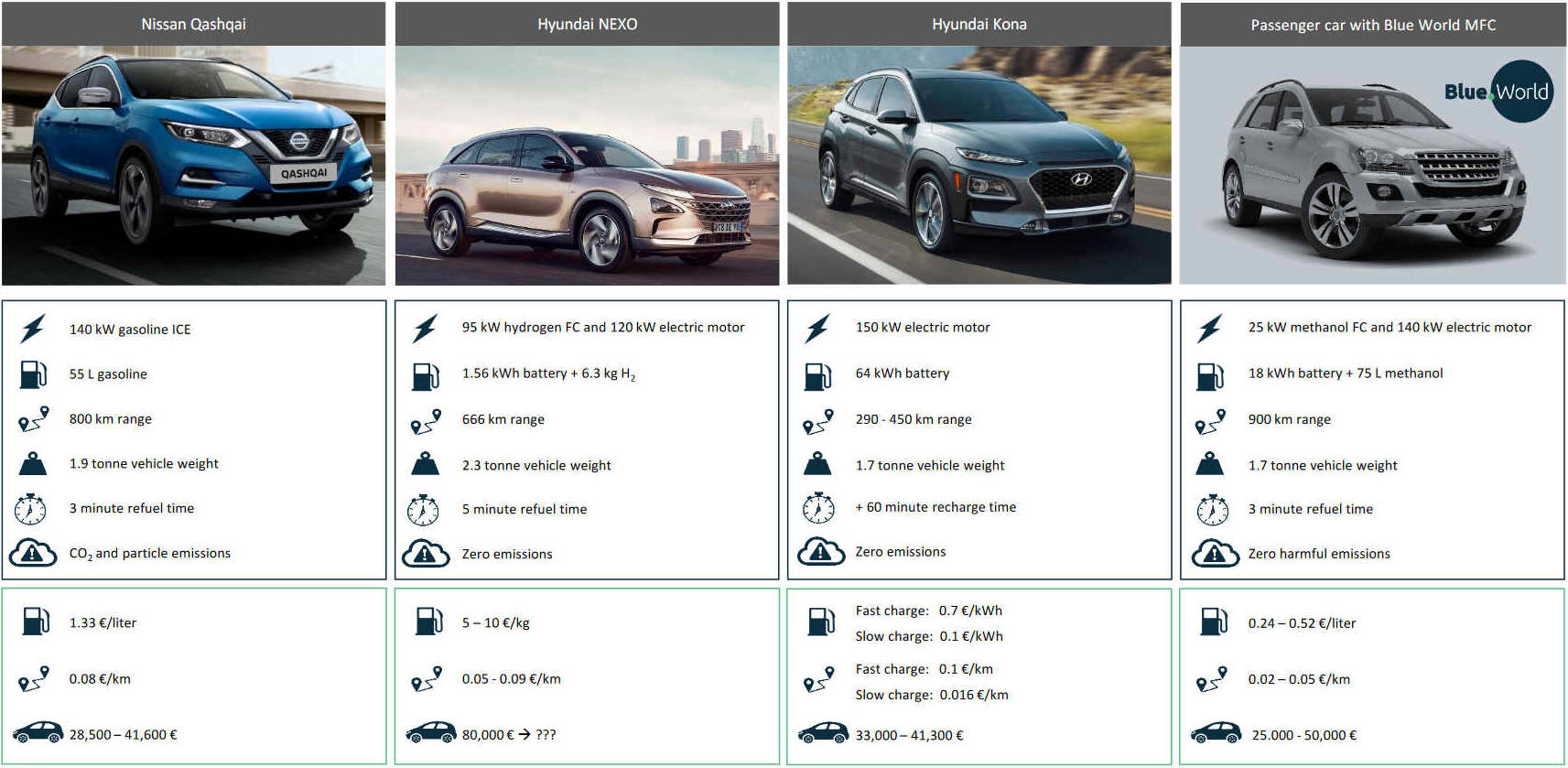

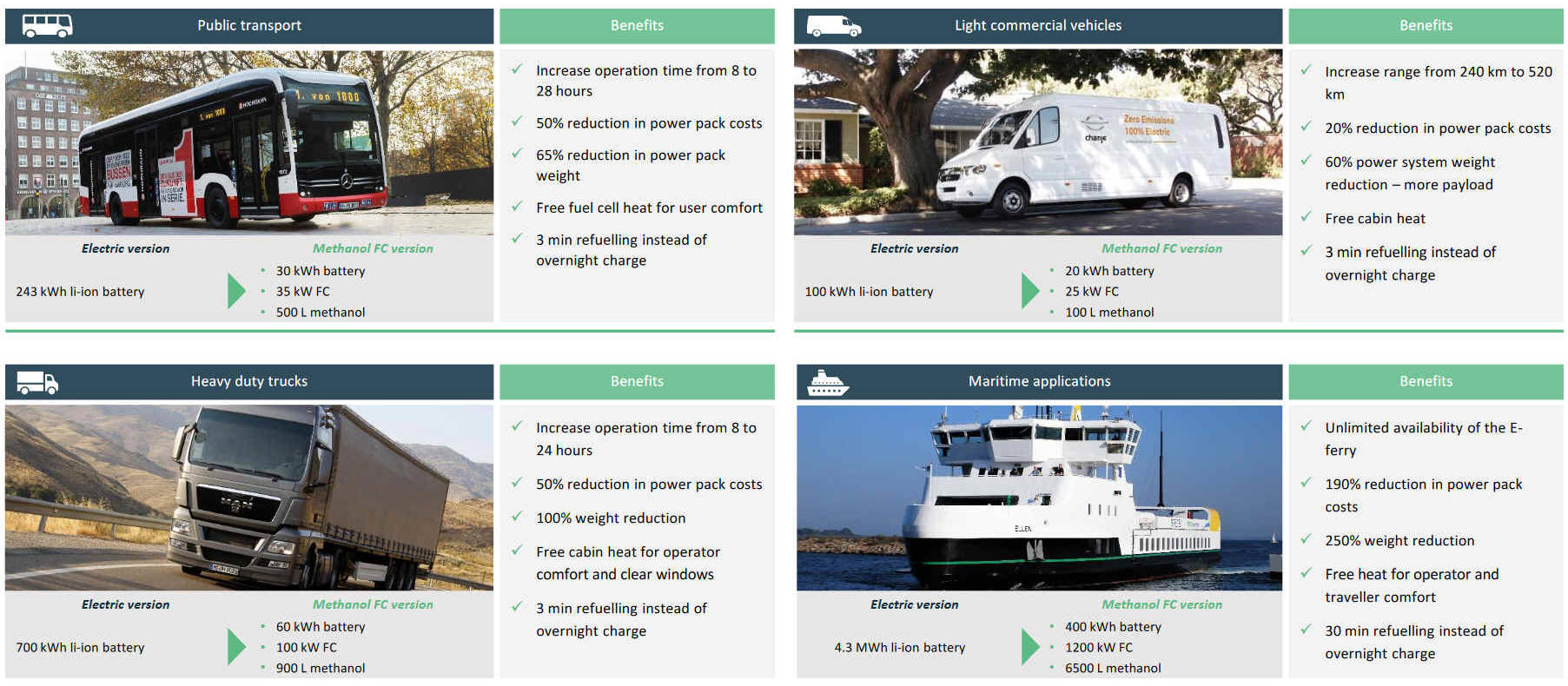

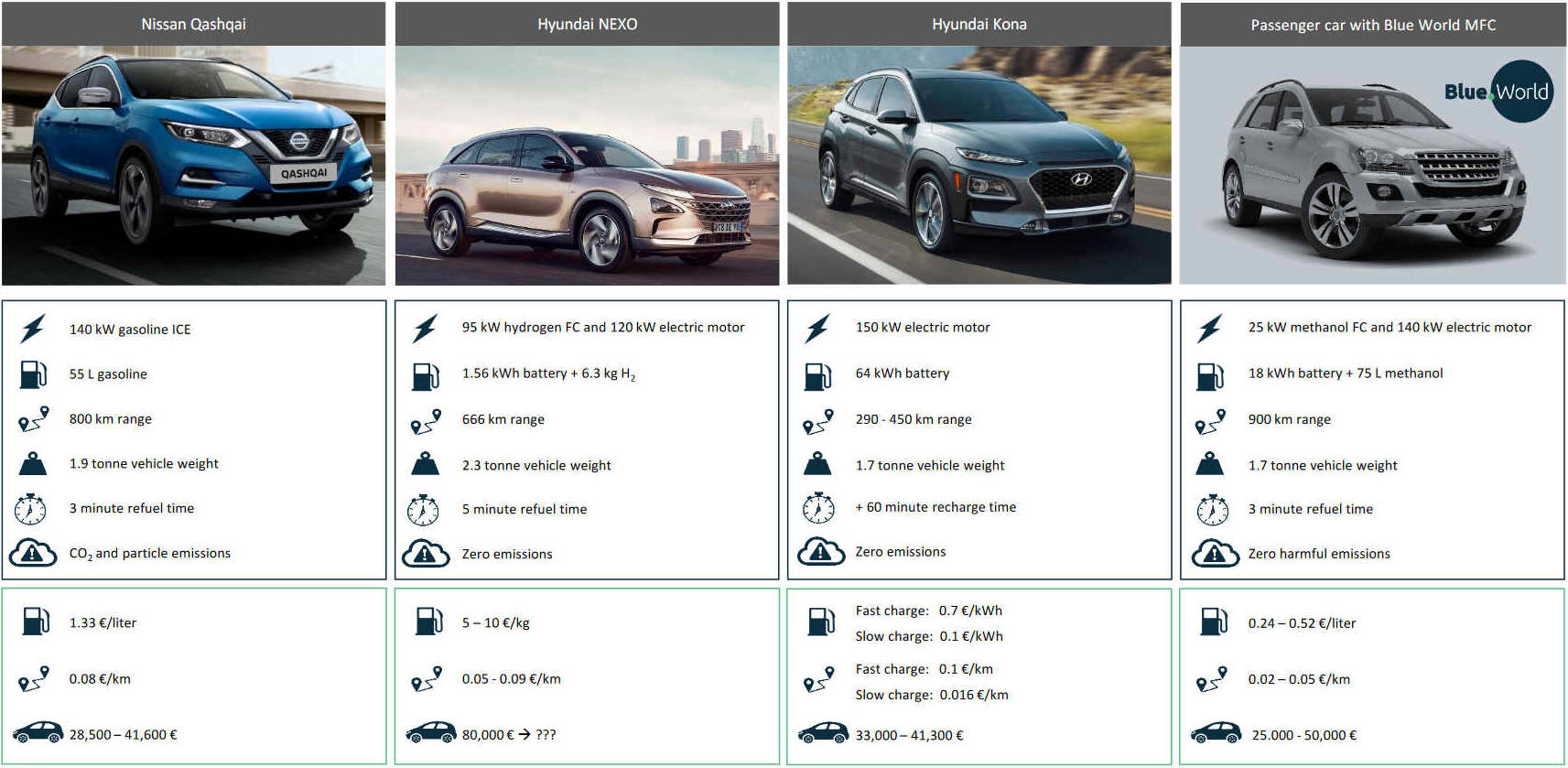

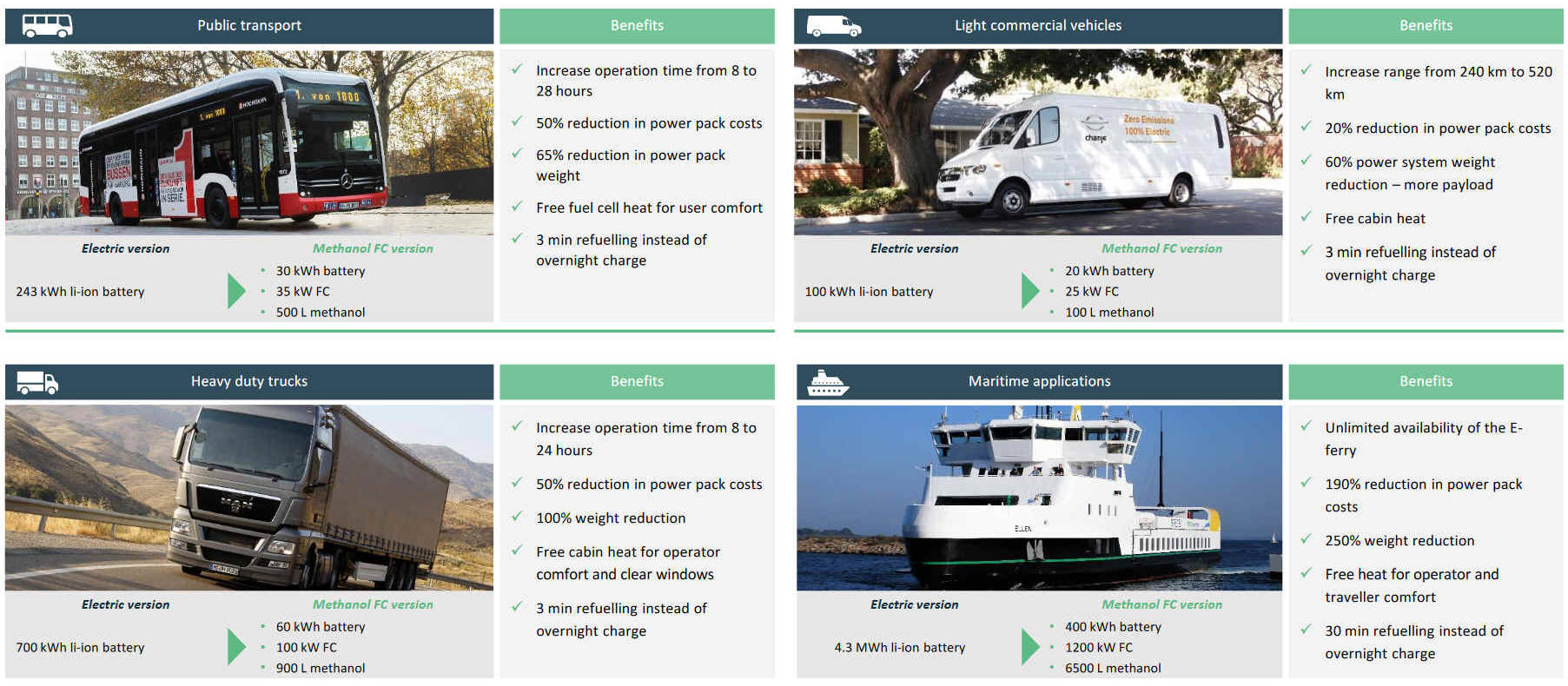

Methanol can be “reformed” on-site at a fueling station to generate hydrogen for fuel cell cars. Or in stationary power units feeding fuel cells for mobile phone towers, construction sites, or ocean buoys. Methanol fuel cells can be fueled just as quickly as your current gasoline or diesel vehicle, and can extend the range of a battery electric vehicle from 200 km to over over 1,000 km.

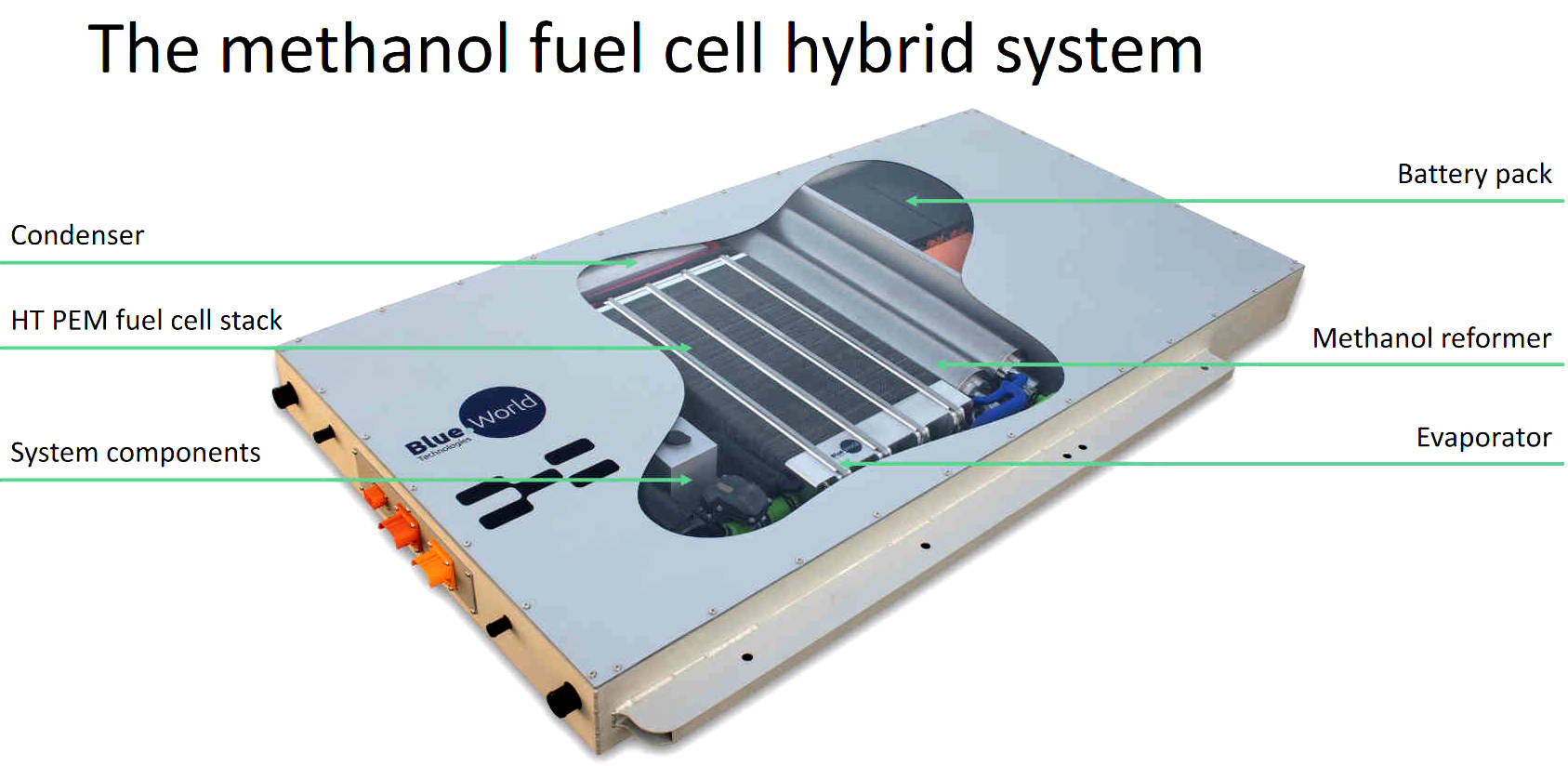

Blue World Technologies, headquartered in Aalborg, Denmark, is an advanced developer and manufacturer of Methanol Fuel cell components and systems for use in mobility and automotive applications. The result is Electric vehicles with 1000km range, 3 min refueling using existing infrastructure and zero harmful emissions.

Mads Friis Jensen, CCO at Blue World Technologies

Mobile: +45 29 70 74 88, e-mail: mfj@blue.world

As potential future maritime fuels go, methanol ticks a lot of the right boxes for vessel owners and operators. It slashes NOx, SOx and particulate emissions; it’s easy to store and handle onboard; and there are already established storage and handling facilities at or nearby most major ports.

FUEL

CELLS

Whichever

of the four proposed solutions, we will use fuel

cells to convert hydrogen to electricity.

DIRECT METHANOL FUEL CELLS

Direct-methanol fuel cells or DMFCs are a subcategory of proton-exchange fuel cells in which methanol is used as the fuel. Their main advantage is the ease of transport of methanol, an energy-dense yet reasonably stable liquid at all environmental conditions.

Whilst the thermodynamic theoretical energy conversion efficiency of a DMFC is 97%; the currently achievable energy conversion efficiency for operational cells attains 30% – 40%. There is intensive research on promising approaches to increase the operational efficiency.

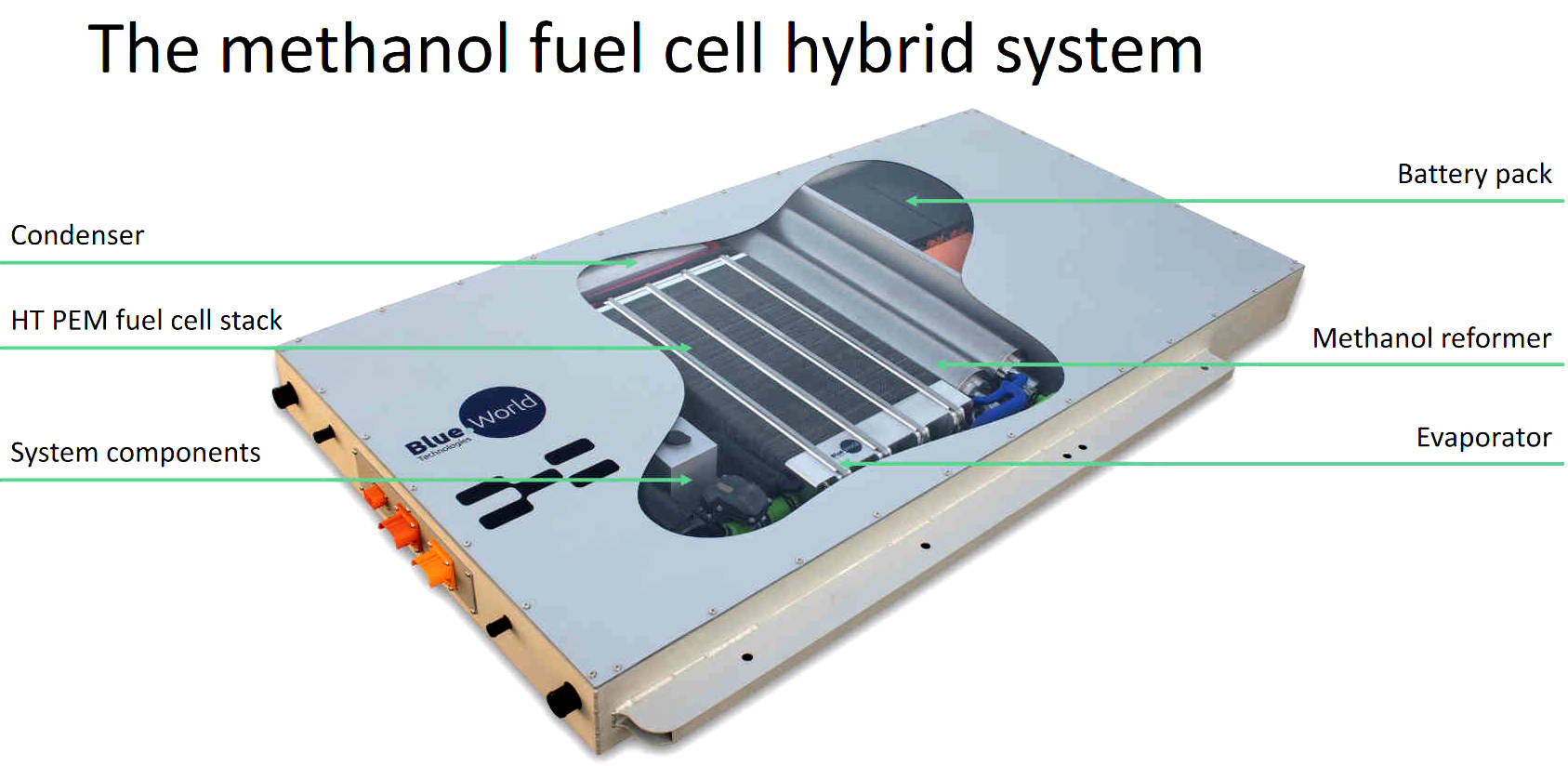

REFORMED OR INDIRECT METHANOL FUEL CELLS RMFC - IMFC

Reformed Methanol Fuel Cell (RMFC) or Indirect Methanol Fuel Cell (IMFC) systems are a subcategory of proton-exchange fuel cells where, the fuel, methanol (CH3OH), is reformed, before being fed into the fuel cell. RMFC systems offer advantages over direct methanol fuel cell (DMFC) systems including higher efficiency, smaller cell stacks, less requirement on methanol purity, no water management, better operation at low temperatures, and storage at sub-zero temperatures because methanol is a liquid from -97.0 °C to 64.7 °C (-142.6 °F to 148.5 °F) and as there is no liquid methanol-water mixture in the cells which can destroy the membrane of DMFC in case of frost. The reason for the high efficiency of RMFC in contrast to DMFC is that hydrogen containing gas is fed to the fuel cell stack instead of methanol and overpotential (power loss for catalytic conversion) on anode is much lower for hydrogen than for methanol. The tradeoff is that RMFC systems operate at hotter temperatures and therefore need more advanced heat management and insulation. The waste products with these types of fuel cells are carbon dioxide and water.

RMFC systems have reached an advanced stage of development. For instance, a small system developed by Ultracell for the United States military, has met environmental tolerance, safety, and performance goals set by the United States Army Communications-Electronics Research, Development and Engineering Center, and is commercially available.

Larger systems 350W to 8 MW are also available for multiple applications, such as power plant generation, backup power generation, emergency power supply, auxiliary power unit (APU) and battery range extension (electric vehicles, ships).

In contrast to diesel or gasoline generators maintenance interval of RMFC systems is usually significantly longer as no exchange of oil-filters and other engine service parts is needed. So the use of RMFC in off-grid applications (e.g. highway maintenance) and remote areas (e.g. telecom, mountains) is often preferred over diesel gensets.

The primary advantage of a vehicle with a reformer is that it does not need a pressurized gas tank to store hydrogen fuel; instead methanol is stored as a liquid. The logistic implications of this are great; pressurized hydrogen is difficult to store and produce. Also, this could help ease the public's concern over the danger of hydrogen and thereby make fuel cell-powered vehicles more attractive. However, methanol, like gasoline, is toxic and (of course) flammable. The cost of the PdAg membrane and its susceptibility to damage by temperature changes provide obstacles to adoption.

COLOURS

OF THE RAINBOW

As with other future fuels, most

notably hydrogen and ammonia, colours are used to denote the sustainability of the different production routes:

GREEN - When methanol is produced using renewable sources like biomass, and if the power used to produce it comes from renewable energy, it is considered to be green methanol.

The greenest form being combining hydrogen with carbon dioxide, so

bypassing the biomass stage.

BLUE - Methanol is a claimed to be a low-carbon method of production from the steam reformation of natural gas, to reduce their carbon footprint by

re-circulating natural gas within the facility, sourcing additional CO2 from a neighbouring industrial facility or using

renewable electricity or

green hydrogen in place of process natural gas.

GREY - Methanol produced from natural gas

BROWN - Methanol produced using coal

WARTSILA

Q & A - FUEL FOR THOUGHT (GREEN METHANOL)

Methanol holds great promise as a future fuel for maritime applications, according to four of Wärtsilä’s leading experts on the topic.

Q: What are the pros and cons of adopting methanol as a future marine fuel?

Toni Stojcevski, General Manager, Sales, Project Services at Wärtsilä:

“Not only does methanol possess ideal physical and chemical properties for combustion engines, but it’s also one of the best options to meet current and future emissions targets. It’s a known quantity in terms of industrial applications and presents a low risk to the environment because it biodegrades rapidly in water. Because methanol is liquid at atmospheric pressure, it can be stored in somewhat similar tanks as traditional diesel onboard a vessel.”

Jussi Mäkitalo, Manager, Business Development at Wärtsilä:

“Converting a vessel to methanol requires approximately double the volume of fuel tank capacity compared to diesel in order to maintain the same level of fuel endurance. Also, methanol tanks require additional cofferdams to prevent any potential leaks into machinery spaces. While finding space for the fuel tanks and fuel handling equipment can be a challenge in conversion projects, Wärtsilä can help to identify the optimal solution as part of a pre-conversion feasibility study.

For conversions, the vessel’s EEXI (Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index) value and CII (Carbon Intensity Indicator) rating is expected to be improved by around 10% when switching from HFO to methanol, if all consumers are converted. However, correction factors are being considered by the IMO that would take into consideration the well-to-wake perspective of the emissions. If adopted these will have some additional impact on the attained EEXI and CII values, depending on whether the vessel is operated with grey, blue or green methanol.”

Q: What about current and future developments in the supply, demand and pricing outlook for methanol?

Greg Dolan, CEO, The Methanol Institute

“Methanol has traditionally been produced and consumed as a chemical feedstock and is relatively new as a marine fuel. We expect production to increase as demand from the shipping industry grows, and a growing proportion of the new supply will be renewable methanol. Since the methanol molecule – CH3OH – is the same whether it is produced from grey, blue or green feedstocks, blending methanol is a viable option to facilitate the transition from conventional to renewable marine fuels.

Analysis conducted by Infiniti Research on behalf of the Methanol Institute has found that methanol is available as a marine fuel at 122 ports around the world.

Waterfront Shipping has stated that using methanol as a fuel resulted in a comparative price per tonne that closely tracked marine gas oil, so for the majority of conventional methanol available today the costs represent a premium that shipowners should find reasonable.

The recent addition of methanol to the Powerzeek Energy Platform was made in response to increased enquiries from shipowners. Powerzeek is an online marketplace that makes it easier for shipowners and trucking companies to find and buy cleaner fuels at the best available price. Both S&P Global Plats and Argus Media are posting methanol marine fuel pricing for the Port of Rotterdam, creating critical pricing benchmarks.”

Q: At what stage is the technology development for using methanol fuel for newbuild vessels?

Paolo Lonzar, General Manager, Product Portfolio, Wärtsilä:

“Wärtsilä is developing a wide range of engine and fuel supply systems to help ship owners navigate the route to reduced greenhouse gas emissions, and we are one of the few marine engine builders to have experience with methanol-fueled engines.

“We have the technology available and running in the field and will further develop it in accordance with customer requirements. Our target is to have a commercially viable 4-5 MW product for newbuilds ready for the market in 2023.”

Q: What about methanol conversions for existing vessels? How easy is the conversion process, and what needs to be taken into account?

Jussi Mäkitalo, Business Development Manager, Wärtsilä:

“A methanol conversion is one way to improve a vessel’s EEXI value and CII rating as well as to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions if using sustainably produced methanol.

“As a first step, vessel owners who are considering a conversion should ensure that they have a clear picture of the methanol availability in their operating area and an understanding of what conversion will mean for their vessel from a business point of view.

“The second step is to carry out a technical feasibility study where we consider the practicalities of converting the vessel. These include which engines would be converted, where to locate the main equipment, how to arrange the fuel storage and piping onboard, and what safety systems are needed and how these will be controlled. Some of the conversion work can be carried out during regular operation of the vessel, but the feasibility of this should be considered on a case-by-case basis.

“It is possible to use any of a vessel’s existing tanks to store the methanol, including void spaces, diesel tanks, ballast tanks, freshwater tanks or other tanks; however, the feasibility of this needs to be checked case by case. On board the Stena Germanica – which was converted to run on methanol in a co-development project between Wärtsilä, Stena Line, the Port of Gothenburg and the Port of Kiel – one of the existing ballast water tanks was converted to store methanol. This tank provided sufficient capacity for the vessel to run on methanol for four round trips, or eight days of operation, while the existing diesel tanks remained untouched, providing fuel redundancy for the vessel.

“From the perspective of onboard safety, there are well-established rules and regulations pertaining to the use of methanol as a marine fuel in the form of MSC.1-Circ.1621 – Interim Guidelines For The Safety Of Ships Using MethylEthyl Alcohol As Fuel. Additionally, at Wärtsilä we have developed a safety concept for methanol engines that acts as a design guideline for all marine projects that involve using methanol as a fuel.”

Jussi Heikkola, Director, Product Management and Technical Information, Wärtsilä:

“We are currently working on our methanol conversion offering and are looking for pilot customers operating with the Wärtsilä 32, Wärtsilä 46 and Wärtsilä 46F engines. We already have an established conversion solution for our ZA40S engines. At the current rate of development we believe we are on track to convert the first engines during 2023.”

Q: How does Wärtsilä see methanol’s role developing in the future?

Toni Stojcevski:

“We see our role as that of an enabler, a facilitator who can aid the customer in choosing the optimal suite of options to support their specific decarbonisation strategy.

“The regulatory pressures are only going one way, and that is up. Measures like the EU Fit for 55 Package, which aim to achieve a 55% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from 1990 levels by 2030, will have a significant impact on the maritime industry. The package, which is well aligned with Wärtsilä’s decarbonisation strategy, is asking the industry to pick up the change of pace and look beyond tailpipe emissions to take the entire fuel supply chain into account. This is clearly evident in the FuelEU Maritime proposal, part of the Fit for 55 Package, which sets limits for maritime fuels’ GHG intensity and levies fines for non-compliance.

“There’s no doubt that methanol has a fantastic potential as a maritime fuel, and going forward the industry needs a stable, economically viable supply. Today there are more than 30 production sites being planned with a combined capacity of three megatons of methanol that will be produced sustainably using renewable power and from renewable feedstocks.”

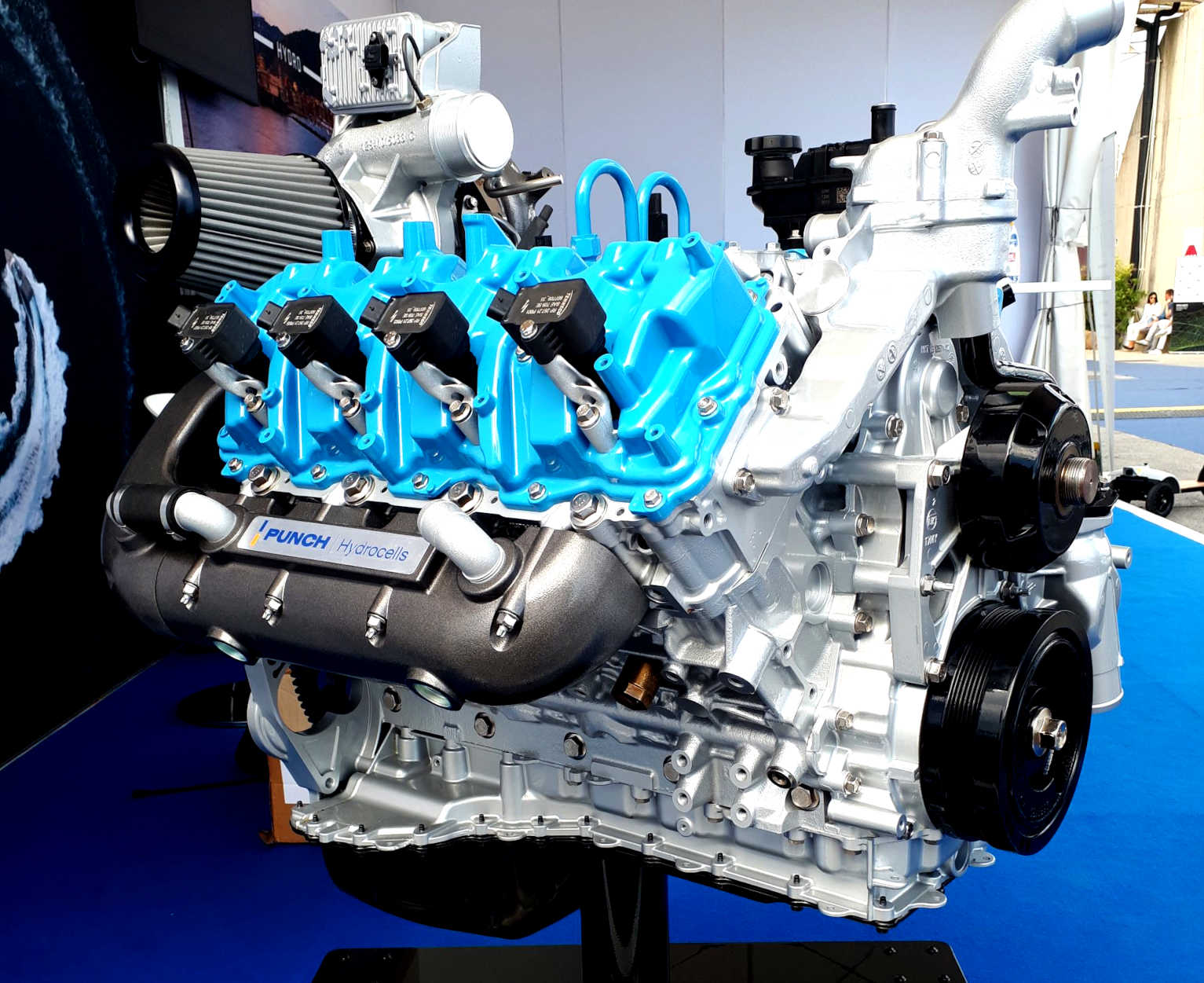

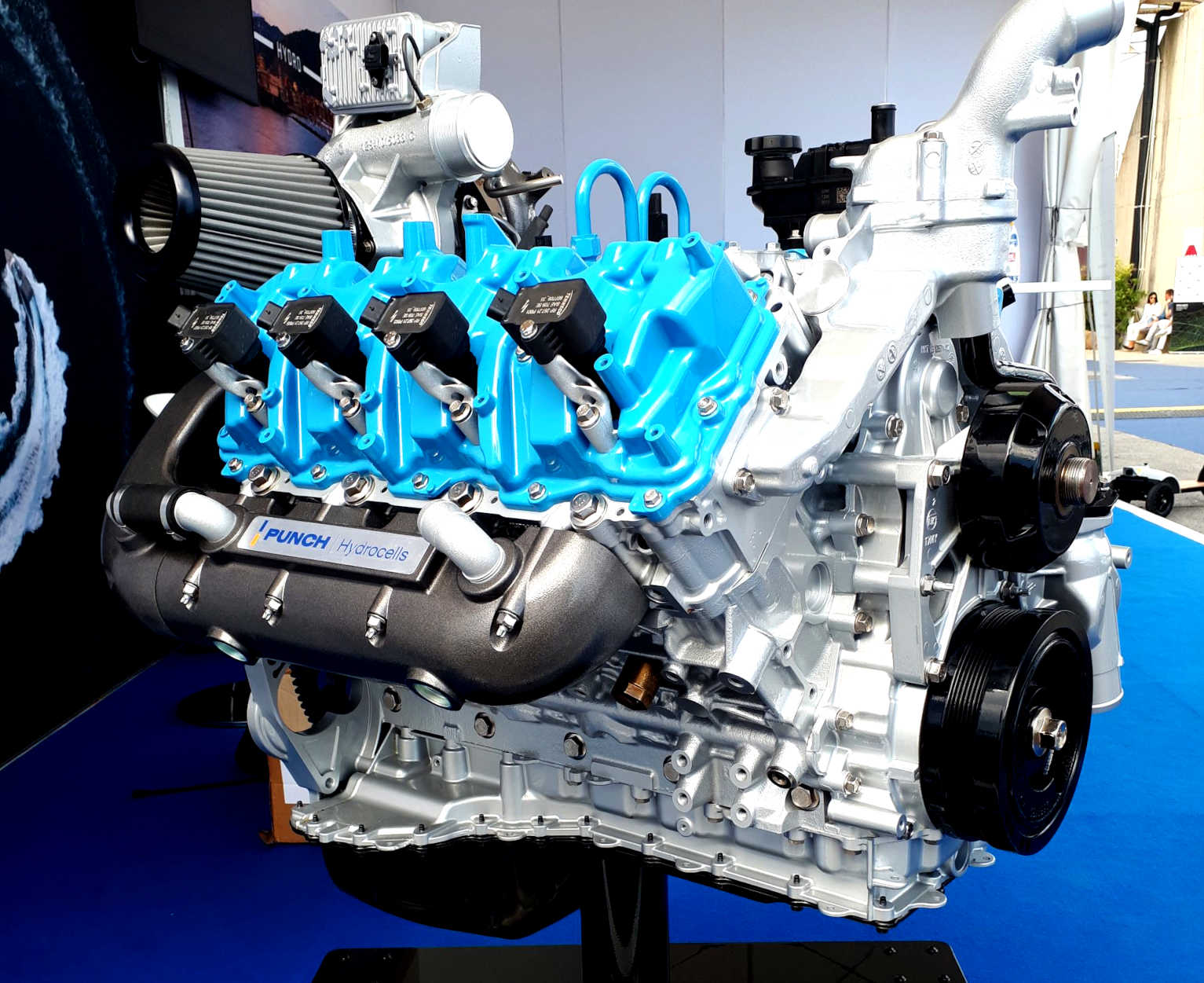

DURAMAX

- Hydrogen fueled diesel engines such as the 6.6 liter unit above, retain

the familiar ICE format and service life limitations with the advantage that ship

operators understand the technology. The, "better the devil we

know" approach, is better than no advance at all.

GUMPERT NATHALIE

The Nathalie is a two-seater coupe, its line is close to the Nissan GT-R. It receives headlights with LEDs at the front, removable shutters and a light strip joining the rear lights. It is designed on a very light carbon shell which gives it high performance with a maximum speed of 300 km/h (190 mph) and a 0 to 100 km/h (62 mph) in 2.5 seconds.

The Nathalie receives four electric motors of 150 kW (200 hp), each placed in the wheels. They develop a combined power of 400 kW (540 hp) transmitted on all four wheels.

The Nathalie is equipped with a 15 kW (20 hp) fuel cell which operates on methanol and supplies a 70 kWh (250 MJ) battery. The complex system developed by RG consists of a methanol reformer which, by a catalyzed chemical reaction, divides methanol into carbon dioxide and hydrogen, the latter feeding the fuel cell which produces electricity. The fuel cell system type is indicated by the fuel cell producer as Reformed methanol fuel cell. It also increases its autonomy thanks to the recovery of energy produced during braking. It benefits from a 60-liter tank of methanol and thus a range of 600 km (370 mi) to 1,200 km (750 mi) in "eco" mode. If renewable methanol (e.g. made of municipal waste or renewable electricity) is used, a carbon-neutral operation is possible.

PRODUCTION - CATALYTIC SYNTHESIS OF METHANOL FROM SYNTHESIS GAS

Methanol is produced from synthesis gas, which has carbon monoxide (CO) and hydrogen gas as its main components. An important advantage of methanol is that it can be made from any resource that can be converted first into synthesis gas. Through gasification, synthesis gas can be produced from anything that is or ever was a plant. This includes biomass,

agricultural and

timber waste, solid municipal waste, and a number of other feedstocks.

If an external source of CO2 is available, the excess hydrogen can be consumed and converted to additional methanol. The most favorable gasification processes are those in which the surplus hydrogen is “burnt” to water, during which steam reforming is accomplished through the following partial oxidation reaction:

CH4 + ½O2 -> CO + 2 H2 -> CH3OH

CH4 + O2 -> CO2 + 2 H2

The carbon dioxide and hydrogen produced in the last equation would then react with additional hydrogen from the top set of reactions to produce additional methanol. This gives the highest efficiency but maybe an additional capital cost.

Unlike the reforming process, the synthesis of methanol is highly exothermic, taking place over a catalyst bed at moderate temperatures. Most plant designs make use of this extra energy to generate the electricity needed in the process.

PORT

OF ANTWERP JUNE 23 2021

The Port of Antwerp is converting a tug to methanol propulsion as part of the European Union-funded Fastwater project, which aims to demonstrate the feasibility of methanol as a sustainable marine fuel in internal combustion engines, as opposed to fuel cells.

The project was set up by a group of European maritime research and technology leaders, and is funded by the European research and innovation programme, Horizon 2020.

Partners in this project include Belgian engineering company Multi, which carried out the feasibility study for the project, Swedish shipbuilder Scandinaos, which designed the vessel’s modifications, ABC (Anglo Belgian Corporation), which will be responsible for converting the engine and for installing the methanol tanks and pipes, while the German company Heinzmann is adapting the injectors.

“This methatug is a further and also an important step in the transition towards a sustainable and CO2-neutral port that has enabled us to overcome a variety of technical and regulatory challenges. Thanks to projects such as this, we are paving the way and hope to be an example and a source of inspiration for other ports,” Jacques Vandermeiren, CEO of Port of Antwerp, said.

The European Commission approved the project in June, after an 18-month-long clearance process and detailed negotiations. Namely, Rhine-based inland navigation craft must comply with the Central Commission for Navigation on the Rhine’s (CCNR) regulations, which had previously forbidden the use of methanol as a marine fuel.

To receive the necessary dispensation, the methatug project was therefore submitted to the CESNI, the European committee that administers overall standards for inland navigation.

The methatug project, described by the port as the world’s first of its kind, is expected to be operational in early 2022.

“Just like with the hydrotug, the hydrogen tugboat, this project confirms our pioneering role in the field of energy transition. The ecosystem of the Antwerp port platform forms an ideal, large-scale testing ground for a project of this type,” Annick De Ridder, port alderwoman, commented.

The Port of Antwerp aims to have one hydrogen-powered tug in 2023 as part of its strategy of becoming a sustainable and CO2-neutral port.

Antwerp-based Compagnie Maritime Belge (CMB) has been hired for the construction of the Hydrotug, which will be driven by combustion engines that burn hydrogen in combination with diesel - so not carbon neutral, but a useful stepping stone.

SVITZER

& MAERSK NOVEMBER 2021

Svitzer, A.P. Moller - Maersk’s world leading towage operator, today unveiled plans in November 2021 to introduce the world’s first fuel cell tug boat for harbour towage operations. Scheduled to enter operation in Svitzer’s Europe region by Q1 2024, the fuel cell tug will be running on green methanol.

The project aims to jointly explore the combination of methanol fuel cells, batteries, storage/handling systems, electric drives and propulsion units as a carbon neutral alternative to the conventional fossil fuelled propulsion train.

The objective is to extract and apply knowledge and operational experience of methanol feasibility from the near shore small scale tug onto larger ocean-going container vessels.

Ingrid Uppelschoten Snelderwaard, Global COO, Svitzer, is quoted as saying: "Fuel cells will be applicable as main propulsion power for tugs earlier than for larger vessels and, further, the time to build a tug is significantly less than for a container vessel."

The newbuild tug will come with a hybrid electrical propulsion system solution where fuel cells can deliver a specific amount of sustained bollard pull using fuel cells alone, adding additional power from the batteries during the short but often frequent peaks that characterises towage.

The fuel cells can also be used to charge the batteries when the tug is mobilising and when the tug is berthed, minimising the need for expensive shore side charging facilities.

Ole Graa Jakobsen, Maersk Head of Fleet Technology is quoted as saying: "Fuel cell technology could be a disruptor in the maritime technology space, promising high efficiencies and eliminating the need for substantial amounts of pilot ignition fuels while removing harmful emissions."

Mikkel Elbek Linnet - Senior Manager +45 248211 96 Mikkel.Elbek.Linnet@maersk.com

REFERENCES

https://www.methanol.org/

|