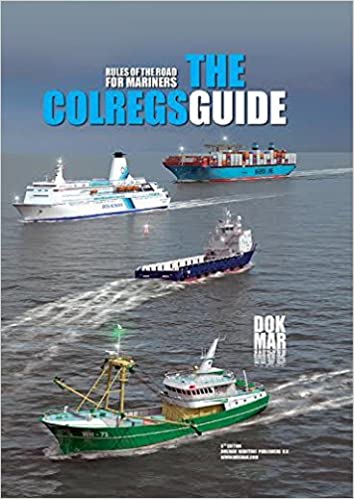

COLREGS

- The Rules are divided into five parts A-E - General Rules (A), Steering and Sailing (B), Lights and Shapes (C), Sound and Light (D) and Exemptions (E).

From 2013 Bluebird Marine Systems lobbied the IMO, asking them if they

planned on changing the rules of the ocean, in light of the possibility

of an autonomous circumnavigation, proposed at that time. The

IMO

replied, that they had no plans to change the rules to accommodate

unmanned waterborne vessels. On that basis, the specification for the

Elizabeth Swann was compiled.

Along

with BMS, who we succeeded, we believe that the rules can and should be

read in conjunction with the IMO's SDGs

in relation to climate

change (SDG13) and the need to reduce harmful emissions from ships

at sea (SDG14). The COLREGs were compiled in 1972, an age away and

wholly out of touch with robotic

and the possibility of solar powered ships, AI,

and the fact that unmanned vessels will outperform a human crew in terms

of persistent monitoring, any day of the week, month or year for that

matter - without food, toilets or sleep. All of this provided that

reliability is greater than we might reasonably expect from a biological

captain. Road vehicles, such as the Google car have demonstrated that autonomous

electric vehicles are more reliable - on their way and inevitable.

This

seems to have escaped the IMO, an organization that some perceive as a

lumbering giant, heading for extinction,

where it seems they cannot keep pace with the real world. Indeed, one might argue

that laws that no longer reflect current practices are of themselves

unlawful. Where laws are man-made, and man has a duty to their fellow

men to provide an effective administration. Hence, where that

effectiveness is lost through inaction or ability to act in good time,

said laws need not be accepted as legally binding. Especially where, in not

allowing safer vessels to compete with vessels less able to cope with

navigation tasks, the IMO are seen to be a Red Flag organization.

Hence, we have compiled a checklist to be sure we have taken account of

the Regulations - and also to assist the IMO with potential policy

revisions. NOTE: This is a voluntary set of actions.

A

good argument in law, by way of a defence against any prosecution, is

that the

IMO would have to prove that an autonomous vessel was inferior and the

party at fault. In a road vehicle, an MOT is required to drive a car or

truck. Such certificate, together with a schedule of maintenance

(Service History) would normally defeat any claim as to negligence, but

causing death by dangerous driving is always an issue for insurers,

nervous about claims. A

robotic ship would always follow a set of rules, where it cannot deviate

in reckless fashion subject to mood swings or substance abuse. In the

case of an accident at sea a counterclaim as to malicious prosecution would be

interesting in setting a case precedent as to duties of authorities. In the UK see the

Wednesbury Rule of Reasonableness in civil litigation and the High Court

ruling as to 'Duty.'

Good

luck with that hypothetical scenario! We'd bet on the robot ship every time.

Hence, for operators of autonomous vessels, don't forget the 'dashcam(s)' for evidence of who was at fault.

Alternatively, operators might register in a

country that is not a contracting party. Outside territorial waters, the

UN have failed to prosecute those dumping fishing

nets and plastic waste from rivers,

where it is the Country that is responsible. Even though this is

illegal!

Regardless

of the perceived lack of policing or advance guidance, as far as the Foundation is

concerned, the

proviso is that any robotic ship is well designed and capable of

operating with at least equal performance, but preferably with superior

reaction times, sight and hearing, fitted with an autonomous navigation system that is

at least as reliable as the best autopilots currently available, and capable

of interacting with its environment with equal or superior clarity to a

human counterpart. This duty rests with the operator of the vessel.

Hence, don't let the unmanned side down by using inferior equipment.

This

falls to be considered more under construction and use regulations - and

certification.

DINOSAURS

BEMCOME EXTINCT - In the opinion of many operators looking to streamline their fleet,

the IMO need to get a grip. More efficient passages, means less

pollution. You do not need a crystal ball to see what lays ahead. It

might pay the incumbents to clean their glasses from time to time. The

dinosaurs could not adapt in time. We wonder if the IMO is capable of

doing that, or is leading us to a collision course with extinction.

That

said, we believe that the Elizabeth

Swann is compliance ready in principle - the first ship in the world to be able to

(substantially) claim to be so.

The 1972 Convention was designed to update and replace the Collision Regulations of 1960 which were adopted at the same time as the 1960 SOLAS Convention.

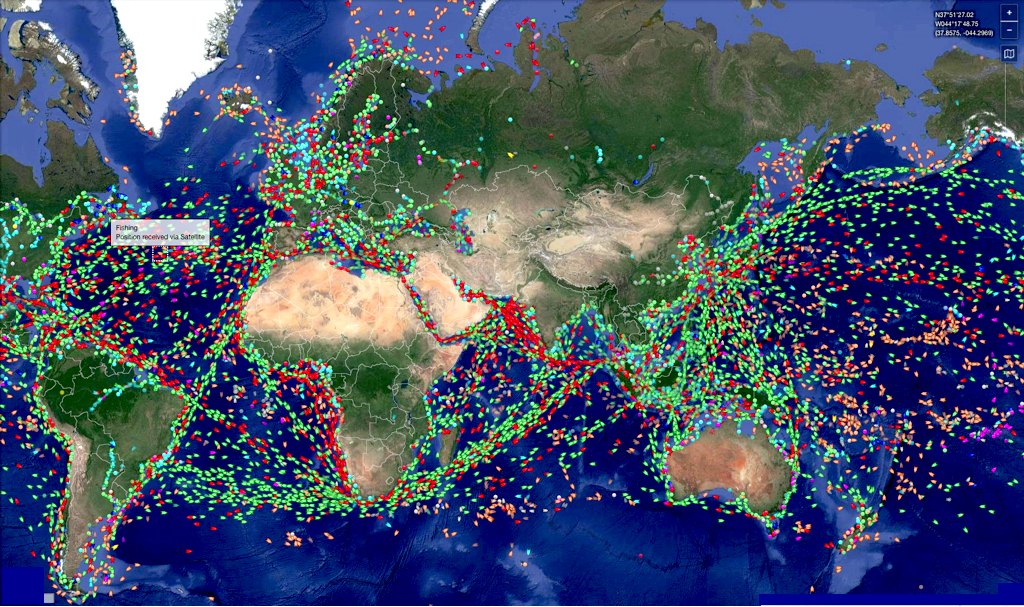

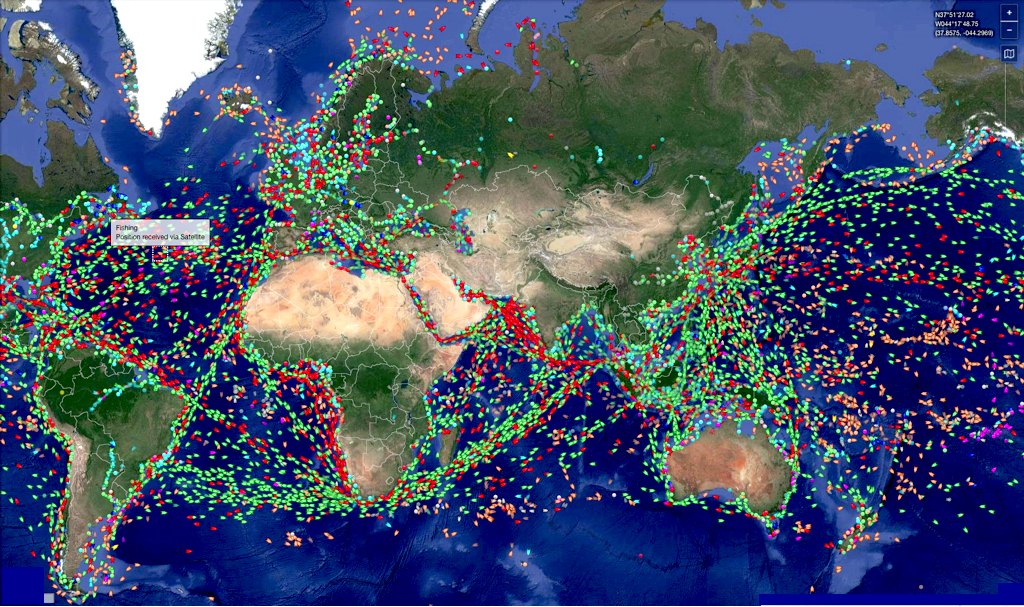

One of the most important innovations in the 1972 COLREGs was the recognition given to traffic separation schemes - Rule 10 gives guidance in determining safe speed, the risk of collision and the conduct of vessels operating in or near traffic separation schemes.

The first such traffic separation scheme was established in the Dover Strait in 1967. It was operated on a voluntary basis at first but in 1971 the IMO Assembly adopted a resolution stating that that observance of all traffic separation schemes be made mandatory - and the COLREGs

subsequently made this obligation clear.

Mostly,

policy makers follow innovators in all walks of life, for they do not

have the vision or the expertise to be able to see ahead of the current

state of play. If they did, they'd be the innovators. For

this reason it is up to engineers and scientists to pave the way for our

political administrations.

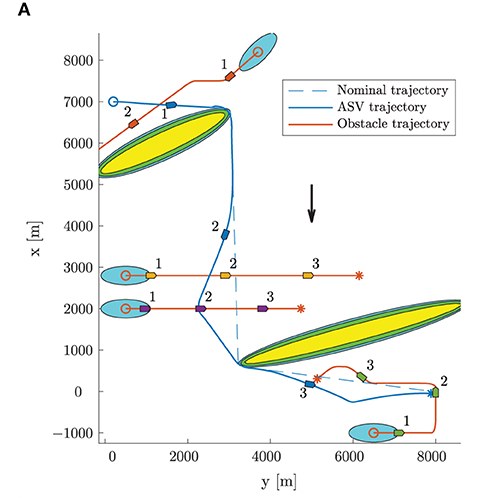

FEBRUARY

2020 Department of Engineering Cybernetics, Centre for Autonomous Marine Operations and Systems, Norwegian University of Science and Technology,

Trondheim, Norway

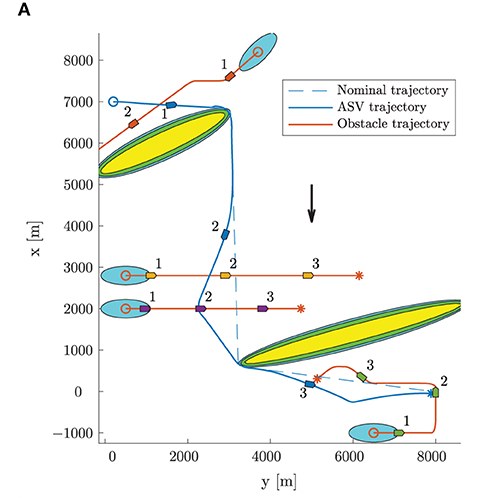

Hybrid Collision Avoidance for ASVs Compliant With COLREGs Rules 8 and 13–17

Bjørn-Olav H. Eriksen*, Glenn Bitar, Morten Breivik and Anastasios M. Lekkas

This paper presents a three-layered hybrid collision avoidance (COLAV) system for autonomous surface vehicles, compliant with rules 8 and 13–17 of the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREGs). The COLAV system consists of a high-level planner producing an energy-optimized trajectory, a model-predictive-control-based mid-level COLAV algorithm considering moving obstacles and the COLREGs, and the branching-course model predictive control algorithm for short-term COLAV handling emergency situations in accordance with the

COLREGs.

Previously developed algorithms by the authors are used for the high-level planner and short-term COLAV, while

those in this paper further develop the mid-level algorithm to make it comply with COLREGs rules 13–17. This includes developing a state machine for classifying obstacle vessels using a combination of the geometrical situation, the distance and time to the closest point of approach (CPA) and a new CPA-like measure.

The performance of the hybrid COLAV system is tested through numerical simulations for three scenarios representing a range of different challenges, including multi-obstacle situations with multiple simultaneously active COLREGs rules, and also obstacles ignoring the COLREGs. The COLAV system avoids collision in all the scenarios, and follows the energy-optimized trajectory when the obstacles do not interfere with it.

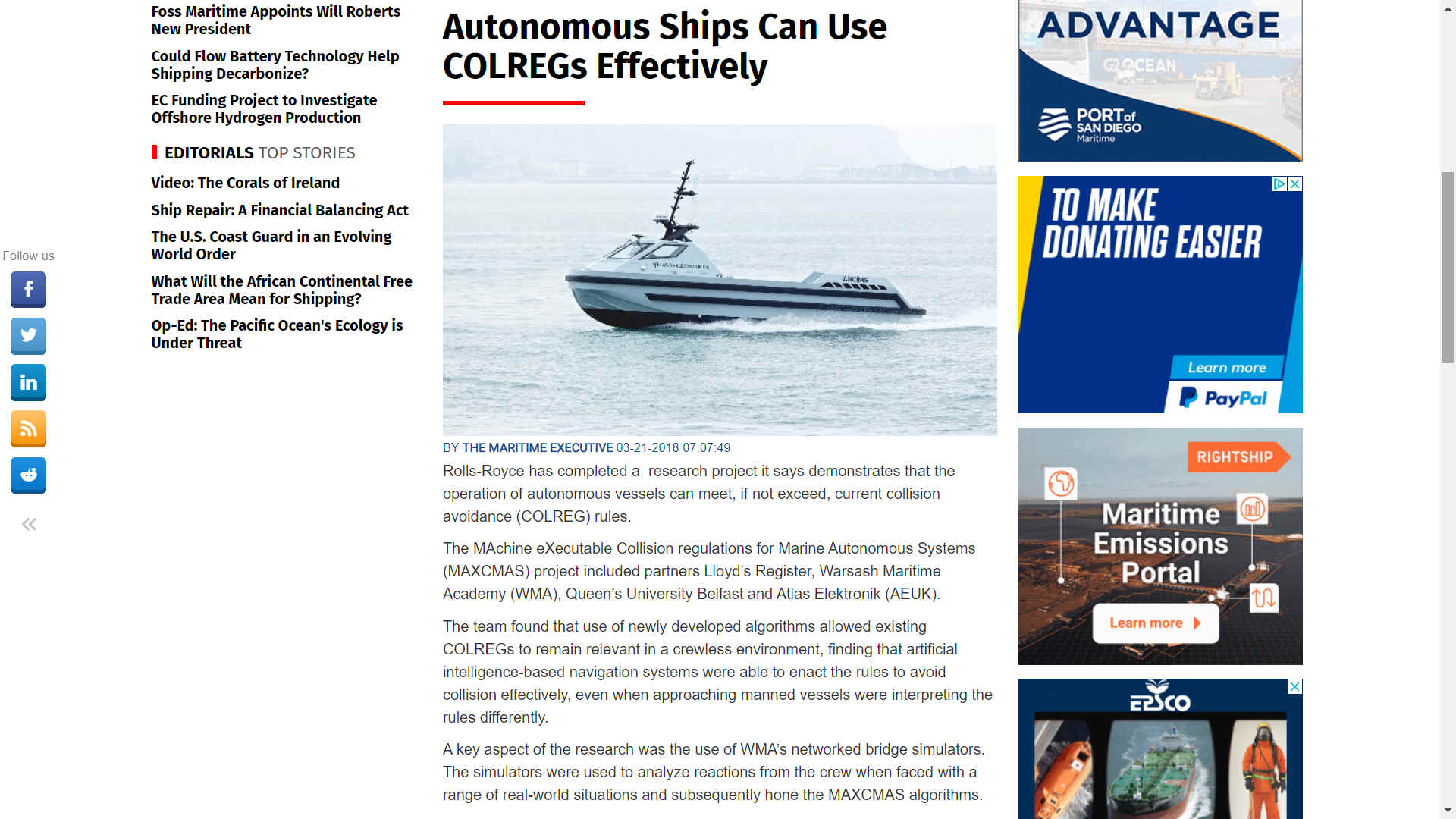

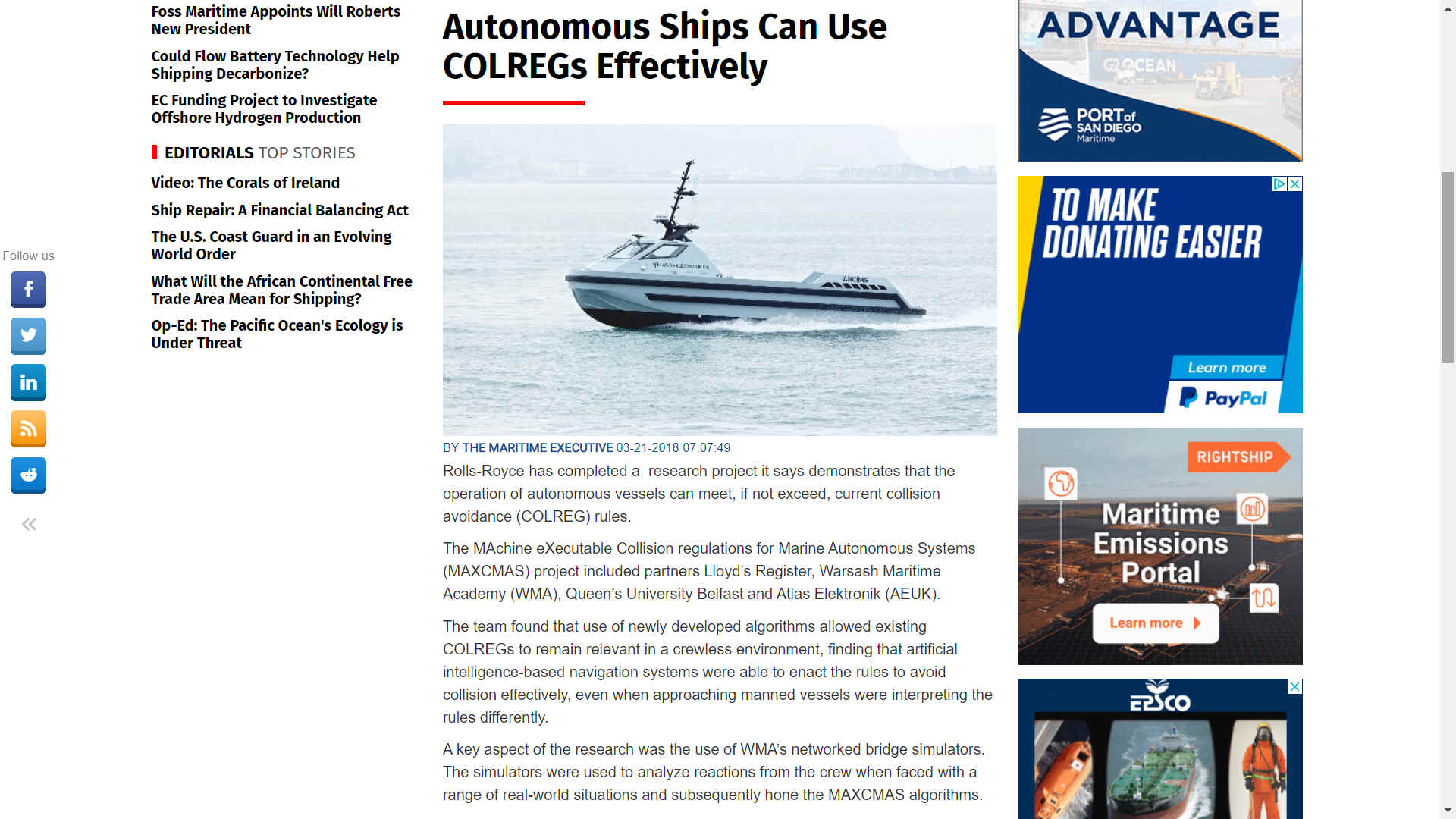

ROLLS

ROYCE MARCH 2018 - AUTONOMOUS VESSELS CAN MEET COLREGS

Rolls-Royce has completed a research project it says demonstrates that the operation of autonomous vessels can meet, if not exceed, current collision avoidance (COLREG) rules.

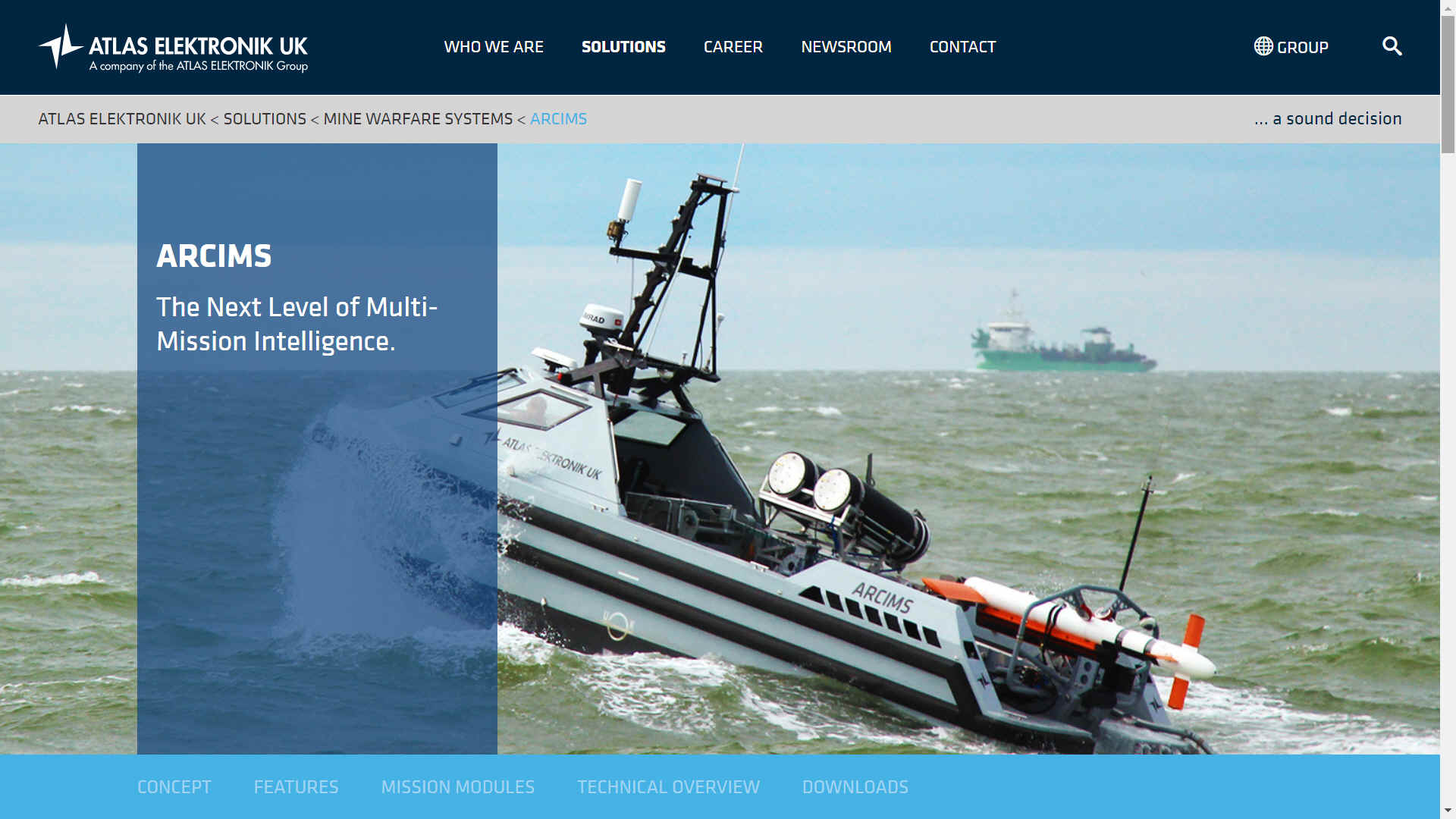

The MAchine eXecutable Collision regulations for Marine Autonomous Systems (MAXCMAS) project included partners Lloyd’s Register, Warsash Maritime Academy (WMA), Queen’s University Belfast and Atlas Elektronik (AEUK).

The team found that use of newly developed algorithms allowed existing COLREGs to remain relevant in a crewless environment, finding that artificial intelligence-based navigation systems were able to enact the rules to avoid collision effectively, even when approaching manned vessels were interpreting the rules differently.

A key aspect of the research was the use of WMA’s networked bridge simulators. The simulators were used to analyze reactions from the crew when faced with a range of real-world situations and subsequently hone the MAXCMAS algorithms.

Rolls-Royce Future Technologies Group’s Eshan Rajabally, who led the project, said: “Through MAXCMAS, we have demonstrated autonomous collision avoidance that is indistinguishable from good seafarer behavior, and we’ve confirmed this by having WMA instructors assess MAXCMAS exactly as they would assess the human.”

During the development project, Rolls-Royce and its partners adapted a commercial-specification bridge simulator as a testbed for autonomous navigation. This was also used to validate autonomous seafarer-like collision avoidance in likely real-world scenarios. Various simulator-based scenarios were designed, with the algorithms installed in one of WMA’s conventional bridge simulators. This also included Atlas Elektronik’s ARCIMS mission manager Autonomy Engine, Queen’s University Belfast’s Collision Avoidance algorithms and a

Rolls-Royce interface.

During sea trials aboard AEUK’s ARCIMS unmanned surface vessel, collision avoidance was successfully demonstrated in a real environment under true platform motion, sensor performance and environmental conditions.

“The trials showed that an unmanned vessel is capable of making a collision avoidance judgment call even when the give-way vessel isn’t taking appropriate action,” said Ralph Dodds, Innovation & Autonomous Systems Programme Manager at AEUK. “What MAXCMAS does is make the collision avoidance regulations applicable to the unmanned ship.”

The MAXCMAS technology and system has been thoroughly tested both at sea and under a multitude of scenarios using desktop and bridge simulators, says

Rolls-Royce, proving that autonomous navigation can meet existing COLREG requirements.

WARMONGERS

- Its a real shame that only the military seem to get priority funding

for such projects in the UK, USA and other G20 members. What the world

needs is more transparency, not more closed shop cloak and dagger. Such

concerns are not equal opportunity employers, openly discriminating in

society. Ultimately, it matters not who think they rule the world. Food

supply is the lowest common denominator. If you cannot feed the growing

population, it is civil war and mayhem. Forget world domination. The UK

is just as bad in Human

Rights terms, as the worst dictatorships. The only difference is the

UK (effectively) kills slowly as in Article 3 ECHR mental

torture and Article 14 castration

(Art 7 UNHR). What is worse, a soldiers death, or continuous

torture. Scotland Yard mercilessly tortured and imprisoned the

Suffragettes, in seeking to quash equality.

MAXCMAS project: Autonomous COLREGs compliant ship navigation. In

Proceedings of the 16th Conference on Computer Applications and Information Technology in the Maritime

Industries (COMPIT) 2017 (pp. 454-464)

Jesus Mediavilla Varas, Spyros Hirdaris, Renny Smith, Paolo Scialla, Walter Caharija, Zakirul Bhuiyan, Terry Mills, Wasif Naeem, Liang Hu, Ian Renton, David Motson, Eshan Rajabally

School of Electronics, Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

This paper discusses the concept and results of the MAXCMAS project, an approach to COLREGs compliance for autonomous ship

navigation. In addition to desktop testing, the system is being implemented and tested thoroughly on networked bridge simulators as well as on an unmanned surface vessel. Both bridge simulation-based and desktop-based results exhibit suitable collision avoidance actions in a one-on-one and multivessel ship encounters respectively. The eventual aim of the project is to demonstrate an advanced autonomous ship navigation concept and bring it to a higher technology readiness level, closer to market.

Title of host publication: Proceedings of the 16th Conference on Computer Applications and Information Technology in the Maritime Industries (COMPIT) 2017

Pages: 454-464

Number of pages: 11

Publication status: Published - 10 May 2017

Event: 16th International Conference on Computer Applications and Information Technology in the Maritime Industries - Cardiff, United Kingdom

Duration: 15 May 2017 → 17 May 2017

TECHNICAL PROVISIONS

The COLREGs include 41 rules divided into six sections: Part A - General; Part B - Steering and Sailing; Part C - Lights and Shapes; Part D - Sound and Light signals; Part E - Exemptions; and Part F - Verification of compliance with the provisions of the Convention. There are also four Annexes containing technical requirements concerning lights and shapes and their positioning; sound signalling appliances; additional signals for fishing vessels when operating in close proximity, and international distress signals.

THESE

ARE THE REGULATIONS:

Part A - General (Rules 1-3)

Rule 1 states that the rules apply to all vessels upon the high seas and all waters connected to the high seas and navigable by seagoing vessels.

Rule 2 covers the responsibility of the master, owner and crew to comply with the rules.

Rule 3 includes definitions of water craft.

Part B- Steering and Sailing (Rules 4-19)

Section 1 - Conduct of vessels in any condition of visibility (Rules 4-10)

Rule 4 says the section applies in any condition of visibility.

Rule 5 requires that "every vessel shall at all times maintain a proper look-out by sight and hearing.

Rule 6 deals with safe speed.

Rule 7 covering risk of collision, which warns that "assumptions shall not be made on the basis of scanty information, especially scanty radar

information."

Rule 8 covers action to be taken to avoid collision.

Rule 9

vessels proceeding in narrow channels should keep to starboard.

Rule 10 of the Regulations deals with the behaviour of vessels in or near traffic separation schemes.

Ships crossing traffic lanes are required to do so "as nearly as practicable at right angles to the general direction of traffic flow."

Section II - Conduct of vessels in sight of one another (Rules 11-18)

Rule 11 says the section applies to vessels in sight of one another.

Rule 12 states action to be taken when two sailing vessels are approaching one another.

Rule 13 covers overtaking - the overtaking vessel should keep out of the way of the vessel being overtaken.

Rule 14 deals with head-on situations. Crossing situations are covered by Rule 15 and action to be taken by the give-way vessel is laid down in Rule 16.

Rule 17 deals with the action of the stand-on vessel, including the provision that the stand-on vessel may "take action to avoid collision by her manoeuvre alone as soon as it becomes apparent to her that the vessel required to keep out of the way is not taking appropriate action.

Rule 18 deals with responsibilities between vessels and includes requirements for vessels which shall keep out of the way of others.

Section III - conduct of vessels in restricted visibility (Rule 19)

Rule 19 states every vessel should proceed at a safe speed adapted to prevailing circumstances and restricted visibility. A vessel detecting by radar another vessel should determine if there is risk of collision and if so take avoiding action. A vessel hearing fog signal of another vessel should reduce speed to a minimum.

Part C Lights and Shapes (Rules 20-31)

Rule 20 states rules concerning lights apply from sunset to

sunrise.

Rule 21 gives definitions.

Rule 22 covers visibility of lights - indicating that lights should be visible at minimum ranges (in nautical miles) determined according to the type of vessel.

Rule 23 covers lights to be carried by power-driven vessels underway.

Rule 24 covers lights for vessels towing and pushing.

Rule 25 covers light requirements for sailing vessels underway and vessels under oars.

Rule 26 covers light requirements for fishing vessels.

Rule 27 covers light requirements for vessels not under command or restricted in their ability to manoeuvre.

Rule 28 covers light requirements for vessels constrained by their draught.

Rule 29 covers light requirements for pilot vessels.

Rule 30 covers light requirements for vessels anchored and aground.

Rule 31 covers light requirements for seaplanes

Part D - Sound and Light Signals (Rules

32-37)

Rule 32 gives definitions of whistle, short blast, and prolonged blast.

Rule 33 says vessels 12 metres or more in length should carry a whistle and a bell and vessels 100 metres or more in length should carry in addition a gong.

Rule 34 covers manoeuvring and warning signals, using whistle or lights.

Rule 35 covers sound signals to be used in restricted visibility.

Rule 36 covers signals to be used to attract attention.

Rule 37 covers distress signals.

Part E - Exemptions (Rule

38)

Rule 38 says ships which comply with the 1960 Collision Regulations and were built or already under construction when the 1972 Collision Regulations entered into force may be exempted from some requirements for light and sound signals for specified periods.

Part F - Verification of compliance with the provisions of the Convention

(Rules 39

- 41)

The Rules, adopted in 2013, bring in the requirements for compulsory audit of Parties to the Convention.

Rule 39 provides definitions.

Rule 40 says that Contracting Parties shall use the provisions of the Code for Implementation in the execution of their obligations and responsibilities contained in the present Convention.

Rule 41 on Verification of compliance says that every Contracting Party is subject to periodic audits by

the IMO.

ANNEXES

The COLREGs include four annexes:

Annex I - Positioning and technical details of lights and shapes

Annex II - Additional signals for fishing vessels fishing in close proximity

Annex III - Technical details of sounds signal appliances

Annex IV - Distress signals, which lists the signals indicating distress and need of assistance.

TOP

TEN REASONS FOR ACCIDENTS AT SEA

The health of the

blue economy is tied significantly to the safety of maritime

transportation. Taking steps to reduce the number of maritime accidents is beneficial

for the safety of human life and equipment and the prosperity of any nation’s

economy.

A Report by the

US's National Transport Safety Board (NTSB) in 2016 outlined the top ten reasons for accidents at sea:

1. Fatigue

The NTSB report indicates that fatigue is one of the most common reasons for transportation accidents, and reducing this cause is a top priority. Mariners should be aware of how sleep loss affects their performance and should refrain from accepting a watch while in a state of fatigue that renders them unfit for duty. In such instances, mariners should prearrange for another qualified individual, i.e. a

watch-stander, to serve in their place when possible. If this is not possible, mariners should refuse duty until they are adequately rested and able to safely execute their responsibilities.

2. Standard Maintenance and Repair Procedures

Very often accidents are simply caused by the failure of one or more individuals to operate according to standardized procedures involving testing, repair and maintenance of equipment. Individuals conducting these procedures must use the correct parts and tools and also ensure system integrity and safe equipment operations according to the appropriate specifications.

3. Use of Medication While Operating Vessels

Using medication in an unsafe manner as a member of a maritime crew can have disastrous results. Mariners should consult with an appropriate medical professional prior to using any type of medication, whether over-the-counter or prescribed. Also, the use of certain medications by credentialed mariners may disqualify them from operating a vessel, including alcohol abuse.

4. Operational Testing Procedures

Standardized procedures should always be used when testing equipment. Optimally, the testing should be performed at normal operating pressures and loads – this can help verify the reliability and quality of the repair or maintenance work performed. All sensors and alarms within vessels should be tested routinely to verify the reliability of their operation and their capability of providing adequate warning to crew members.

5. Familiarization with Local Recommendations

It’s important for vessel operators to have familiarity with and heed the recommendations of local specialists in the maritime industry as well as pertinent publications, including the United States Coast Pilot and others. Failure to do so may result in unnecessary accidents.

6. Underestimating Strong Currents

Mariners can face significant challenges when operating in high water with currents that are more powerful than normal. Under such conditions, the ability to maneuver may be diminished significantly and the risk of parting lines or dragging anchor may be increased. It’s vital for operators and owners to encourage their mariners to properly assess dangers, and remain aware of prevailing conditions. As well, they must take into consideration the guidance of authoritative entities such as the Coast Guard – and from this information takes steps to minimize risks. In particular, the “downstreaming” maneuver often performed by inland towers is risky when strong currents are present.

7. Bridge Resource Management

When pilots are faced with limited reaction times and hazards are close at hand, it’s important to have all possible resources available for use in order to help ensure the safe operation of vessels, including human resources and equipment. The utilization of these resources falls under Bridge Resource Management.

8. Proper Safety Equipment

It’s vital that owners, operators and crewmembers of a vessel do their part to ensure the proper maintenance and functioning of safety equipment on the vessel. As well, they should ensure the vessel is equipped with the necessary safety equipment to handle emergencies and provide the best chance of survival for all on board.

SMART PHONE

APP

- You can now get an app for your android or iphone for free.

9. Distractions

A very high priority as it concerns safety improvements involves the minimization of distractions. Although it is necessary for operators to communicate with dispatchers and crewmembers as well as conduct other work duties involving the checking of equipment and instruments, anything that hinders proper vessel operation can result in tragic outcomes.

10. Access to High Risk Spaces

The importance of high risk spaces, in particular those with hull penetrations, remaining freely accessible. If these spaces are blocked, a safety hazard exists and operators may be hindered from responding to flooding and other types of emergencies when and if they occur.

How

did this happen? The answer is that they did not have autonomous

navigation aids onboard. They relied on humans.

VESSEL

OPERATION MODE CIRCUIT SELECTIONS

COLLISION

AVOIDANCE PROGRAM - FOR AUTONOMOUS SHIPS

FULLY

COMPLIANT WITH COLREGS

CIRCUIT

KEY:

Autonomous

mode _______ select to engage fully

automatic ship control

Manual

mode

_______ select this to allow an onboard crew to take control

Drone

mode

_______ selection for controlling the ship remotely via satellite

Collision

avoidance

________ disengages autopilot when danger arises

Part

A - General (Rules 1-3) & Part B- Steering and Sailing Section 1 -

Conduct of vessels in any condition of visibility (Rules 4-10)

Rule

1 states that the rules apply to all vessels on

the high seas and connected waters.

Rule

2 covers the responsibility of the master, owner

and crew to comply with the rules.

Rule

3 includes definitions of applicable water

craft (vessels).

Rule

4 says the section applies in any conditions of

visibility.

Rule

5 every vessel shall at all times maintain a

proper look-out by sight and hearing.

Rule

6 deals with safe speed.

Rule

7 risk assumptions shall not be made on scanty

(radar) information.

Rule

8 covers action to be taken to avoid collision.

Rule

9 vessels proceeding along a narrow channel should

keep to starboard.

Rule

10 deals with the behaviour of vessels in or near

traffic separation schemes.

Sections

II & III Conduct of Vessels in Sight of one

another

Part

C - LIGHTS & SHAPES (Rules

20-31)

Part

D - SOUND AND LIGHT SIGNALS - DEFINITIONS (Rules

32-37)

Part

E - EXEMPTIONS - Rule

38

Part

F - Convention compliance verification provisions Rules 39

- 41

Annex

I - Positioning and technical details of lights

and shapes

Annex

II - Additional signals for fishing vessels fishing in

close proximity

Annex

III - Technical details of sounds signal

appliances

Annex

IV - Distress signals indicating distress and need

of assistance

International Maritime Organization

(IMO)

4 Albert Embankment, London SE1

7SR

United Kingdom

+44 (0) 20 7735 7611

ARCHINAUTE:

A wonderfully innovative rotary sail catamaran that can head directly into the wind.

The wind turbine generates electricity to drive a propeller via an

electric motor. Ordinary

sailing craft have to tack when beating upwind. This is another example

of a changing world that the IMO, G20

and EC have not anticipated, or made

allowances for.

LINKS

& REFERENCE

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frobt.2020.00011/full

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frobt.2020.00011/full

https://pure.qub.ac.uk/en/publications/maxcmas-project-autonomous-colregs-compliant-ship-navigation

https://www.uk.atlas-elektronik.com/solutions/mine-warfare-systems/arcims.html

https://pure.qub.ac.uk/en/publications/maxcmas-project-autonomous-colregs-compliant-ship-navigation

https://pureadmin.qub.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/129886124/MAXCMAS_paper_2017_submitted.pdf

https://www.professionalmariner.com/rolls-royce-autonomous-vessels-can-meet-colregs/

https://www.maritime-executive.com/article/autonomous-ships-can-use-colreg-rules-effectively

http://inoa.net/zeilen/colreg.html

http://gosailing.info/collision-regulations-colregs/

https://www.blue-growth.org/COLREGS_COLLISIONS_AT_SEA_REGULATIONS_IMO_PREVENTION_CONVENTION_NAVIGATION_RULES.html

http://www.solarnavigator.net/boats/collision_at_sea_regulations_colregs.htm

https://www.rya.org.uk/newsevents/e-newsletters/inbrief/Pages/do-you-know-your-colregs.aspx

https://www.imo.org/en/About/Conventions/Pages/COLREG.aspx

https://www.bluebird-electric.net/COLREGS_International_Regulations_for_Preventing_Collisions_at_Sea_1972.htm