|

On 14 July 2021 the

European Commission adopted the 'fit for 55' package, adapting existing climate and energy legislation to meet the new EU objective of a minimum 55 % reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2030. The fit for 55 package is part of the

European Green

Deal, a flagship of the von der Leyen Commission that aims to put the EU firmly on the path towards climate neutrality by 2050, as set out in the recently agreed European Climate Law (July 2021). One element in the fit for 55 package is the revision of the Renewable Energy Directive (RED II), to help the EU deliver the new 55 % GHG target. Under RED II, the EU is currently obliged to ensure at least 32 % of its energy consumption comes from renewable energy sources (RES) by 2030. The revised RED II strengthens these provisions and sets a new EU target of a minimum 40 % share of RES in final energy consumption by 2030, together with new sectoral targets. In the European Parliament, the file has been referred to the Committee for Industry, Research and Energy, with the Committee on the Environment, Public Health and Food Safety as associated committee under Rule 57. Discussions on the file have also begun in the Council of the EU.

FIT

FOR 55 - A COMPREHENSIVE AND INTERCONNECTED SET OF PROPOSALS 14 JULY 2021

The proposals from July 14th 2021 to enable the necessary acceleration of greenhouse gas emission reductions in the next

decade, was the starting point for the Fit For 55 package. The idea was to combine: application of emissions trading to new sectors and a tightening of the existing EU Emissions Trading System; increased use of renewable energy; greater energy efficiency; a faster roll-out of low emission transport modes and the infrastructure and fuels to support them; an alignment of taxation policies with the

European Green Deal objectives; measures to prevent carbon leakage; and tools to preserve and grow our natural carbon sinks.

REVISION

OF THE RENEWABLE ENERGY DIRECTIVE: FIT FOR 55 PACKAGE - BRIEFING 12-11-2021

EXISTING SITUATION

Directive 2009/28/EC on the promotion of the use of renewable energy sources – better known as the Renewable Energy Directive (RED I) – established a series of measures to help the EU reach its 20 % renewable energy target by 2020, part of the broader 2020 climate and energy package. RED I set binding minimum national targets for all Member States, calculated in terms of the renewable energy sources (RES) share of their gross final energy consumption. These minimum targets varied between Member States (from 10 % in Malta up to 49 % in Sweden) in a way that was collectively sufficient for the EU to meet its overall 20 % target. RED I included the sub-target of a 10% RES share in each Member State's transport sector by 2020, an ambition that has generally not been met. RED I also included several initiatives to support EU and Member States in their promotion of RES, especially on the cross-border dimension (statistical transfers, joint projects, joint support schemes, guarantees of origin). Furthermore, RED I defined in considerable detail the EU sustainability criteria for biofuels and their method of calculation. RED I contained its own reporting and monitoring requirements: Member States had to develop national renewable energy action plans, while the Commission prepared biennial renewable energy progress reports.

Directive (EU) 2018/2001 – better known as RED II – was a full recast of RED I to reflect the goals of the 2030 climate and energy framework, including a 32 % EU renewable energy target by 2030. While RED II did not set new binding targets on individual Member States, the existing 2020 targets remained as binding baseline levels (minimum RES share). The delivery of RED II objectives relies instead on a more integrated process of monitoring, reporting and improving EU and national climate and energy policies under Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 on Governance of the Energy Union.1

The Governance Regulation requires Member States to develop comprehensive 10-year national energy and climate plans (NECPs). NECPs can be updated to reflect shifting EU climate objectives. RED II contains several measures to improve the effectiveness of RES support, in particular cross-border schemes (see above) that so far have had limited impact, together with provisions to speed up the granting of permits for new RES installations. RED II set a new 14 % sub-target for the share of RES in the transport sector, with further sub-targets to promote advanced biofuels and phase out support for biofuels considered environmentally unsustainable (e.g. imported palm oil). RED II contains more stringent sustainability and GHG emissions-saving criteria for biofuels, which vary by sector (electricity, heating and cooling, or transport). RED II includes indicative targets to raise the RES share in (district) heating and cooling. Renewable self-consumers and renewable energy communities are legally defined under RED II and targeted for support.

The Commission's latest renewable energy progress report (October 2020), prepared as part of the RED I reporting requirements, gave an updated perspective on how effective the EU has been at meeting its RES targets at EU and Member State level. The report found that in 2018 the EU reached an average RES share of 18 % (18.9 % EU-27),2 well above its indicative trajectory for 2017/2018 (16 %) and putting the bloc on a steady path towards meeting its 2020 goals. Yet whereas electricity and heating and cooling reached a higher than anticipated RES share, progress on transport has been more slow with an 8 % RES share for the EU in 2018 (lower than the 8.5 % indicative trajectory) with only two Member States exceeding the 10 % target (Finland and Sweden).

Bioenergy continues to be the main source of renewable energy in the EU (around 60 %), and the majority of this comes from forestry, raising concerns about sustainability. RES progress has also been uneven, with 22 current Member States above their indicative trajectories while five are below it (Ireland, France, Netherlands, Poland, Slovenia). This poses a high risk that several Member States will fail to meet their 2020 national targets, even if the overall 20 % EU target is delivered. Nevertheless, the NECPs submitted by Member States as part of the Governance Regulation suggest the EU is on track to deliver an above target 33.1 to 33.7 % RES share by 2030.

The European Green Deal significantly raises the EU's climate ambition, with a view to delivering on its multilateral commitments under the Paris Agreement and putting it on a path towards climate neutrality (net zero GHG emissions) by 2050. To achieve this goal, the Commission communication on a 2030 climate target plan proposed a new intermediate target of 55 % GHG emissions reductions by 2030 (up from 40 %), compared with 1990 levels. This new 55 % GHG target was later agreed by Council and Parliament in their interinstitutional negotiations over the European Climate Law (July 2021). According to the impact assessment (IA) underlying the 2030 climate target plan, the new 55 % GHG target will require a 38-40 % RES share in final energy consumption by 2030. This makes it necessary for the EU to revise the RED II and related climate and energy legislation, since these are only oriented towards delivering a 32 % minimum RES share.

PARLIAMENT'S STARTING POSITION

Parliament has expressed support for a RED II reform that sets higher 2030 RES share targets at EU and Member State level.

The resolution of 21 October 2021 on the 2021 UN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, UK (COP26) 'underlines the importance of increasing renewable energy and energy efficiency targets to achieve climate neutrality by 2050 at the latest and to comply with the Paris Agreement'.

Parliament's resolution of 15 January 2020 on the European Green Deal called for RED II to be revised in line with the EU goal of net zero GHG emissions by 2050, which will require the EU to greatly increase its share of renewable energy sources and phase out fossil fuel use.

The resolution of 23 June 2016 on the renewable energy progress report called for the original RED 'to be adapted to comply with the agreed goal of keeping the global temperature increase to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels', as set out in the Paris Climate Change Agreement. The resolution stressed the value of binding national targets in the original RED (2009) and supported their inclusion in the forthcoming revision of the directive (RED II). It also included a series of suggestions about how to improve EU and Member State implementation of the RED.

During interinstitutional negotiations over RED II in 2018, Parliament pushed for the EU to set a binding minimum target of a 35 % RES share in final energy consumption by 2030 (12 % in the transport sector). Member States would need to set national targets that were collectively sufficient to meet this goal. The final compromise in RED II (see EPRS briefing) was a binding 32 % target at EU level, without setting new national targets. The existing 2020 targets would remain as a binding baseline level (minimum share) for each Member State at all times.

During interinstitutional negotiations over the European Climate Law in 2021, Parliament pushed for an EU target of at least 60 % GHG emissions reductions by 2030, significantly more than the 55 % reductions sought by the Commission and the Council. A 60 % GHG target would necessitate greater investment in clean energy sources and a higher share of renewables in the energy mix, and would therefore require a much higher RES target for 2030 than the 32 % share outlined in RED II.

COUNCIL'S STARTING POSITION

The European Council conclusions of December 2020 endorsed a binding EU minimum target of a minimum 55 % reduction in GHG emissions by 2030, which would set the EU on the path towards climate neutrality (net zero GHG emissions) by 2050. The Council of the EU followed through on these high level commitments when it negotiated the European Climate Law in 2021 and tasked the Commission with proposing the necessary measures to achieve these 2030 and 2050 targets, including the required changes to EU climate and energy legislation (including RED II).

PREPARATION OF THE PROPOSAL

In July 2021, the Commission published an impact assessment report of around 400 pages to accompany its legislative proposal to revise RED II, together with a very short executive summary. The IA assessed eight main policy options for aligning RED II with the EU's new climate target.

The Commission's IA concluded that the preferred option was a package of measures, including:

i) a 40 % RES target by 2030 (binding at EU level with indicative national contributions);

ii) increased RES ambition in the heating and cooling and transport sectors via higher sub-targets;

iii) new measures to improve energy system integration (sectoral coupling);

iv) comprehensive terminology and certification of renewable fuels, to be traced through a single Union database;

v) stronger promotion of renewable fuels of non-biological origin (RFNBOs), in particular hydrogen, to be achieved inter alia through new targets;

vi) extension of agricultural biomass no-go areas to cover

forest biomass;

vii) extension of the GHG and sustainability criteria for biofuels that already exist in RED II to cover all existing RES installations (currently, the new criteria in RED II apply only to new installations);

viii) greater cross-border cooperation, initially through pilot projects, with a particular focus on joint development of offshore energy;

ix) various measures to promote the uptake of RES in industry.

The above package was closely reflected in the text of the Commission's legislative proposal.

The Commission submitted its draft IA to the Regulatory Scrutiny Board (RSB) on 10 March 2021, and received an initial negative opinion on 19 April 2021, together with recommendations for improvement. The Commission submitted a second draft IA on 28 April 2021, which received a positive opinion with reservations from the RSB on 28 May 2021. The final IA adopted by the Commission sought to address the numerous reservations of the RSB. Annex 1 of the IA explains in detail the RSB's various recommendations and how these were addressed by the Commission.

In preparation for the legislative proposal, the Commission organised a series of consultations with stakeholders and the general public, as outlined in Part 2 of the IA. First, an inception impact assessment (IIA) was published and opened to feedback between 3 August and 21 September 2020. The IIA received a total of 374 responses from 21 Member States and 7 non-EU countries. The vast majority of contributions supported the climate ambition of the European Green Deal and were in favour of revising RED II, including more ambitious sub-targets for transport, heating and cooling. Several stakeholders identified the need to change RED II to prohibit the use of forest biomass. A small number of stakeholders pointed out the potentially negative impact such an early revision of RED II for the stability of the regulatory framework and investor certainty.

The Commission subsequently organised a broader public consultation between 17 November 2020 and 9 February 2021, using as its basis a detailed questionnaire containing multiple choice and open questions covering a wide range of issues relating to the revision of RED II. This public consultation received a very large number of replies (39,046), although the vast majority consisted of a standard reply to a single question on the types of biomass permitted for bioenergy production. This standard reply was part of a coordinated environmental campaign opposing the use of forest biomass as a RES. 98% of the respondents (38 400) identified as private citizens, while only 2% (670) represented an organisation. The latter generally expressed support for raising the headline target of RED II and making it more binding, expressing particular support for more ambitious sub-targets in the transport sector, with differences of view on biomass.

Stakeholder views were further refined in two policy workshops organised by the Commission on 11 December 2020 and 22 March 2021. Both took place online and registered numerous participants (around 500 for the first workshop, close to 1 000 for the second workshop). Stakeholders were also consulted in specialised forums such as the Gas Regulatory Forum (14-15 October 2020), expert workshops on the decarbonisation of heating and cooling (26 November 2020 and 5 February 2021) and the Florence Electricity Forum (7 December 2020). Finally, consultations with the relevant sectoral social partners were held in a specific hearing on the 'fit for 55' package held by Executive Vice-President Frans Timmermans and Commissioner Nicolas Schmit on 1 July 2021.

EPRS carried out an implementation appraisal of RED II on behalf of the European Parliament in March 2021. This looked at how the EU and its Member States had been meeting the goals set out in RED I and how they had progressed in terms of implementation of RED II. It also summarised some of the key views expressed by the European Parliament, other EU bodies and selected stakeholders.

The Commission (DG Energy) sponsored several external studies on the revision of RED II,3 as well as recent studies on offshore energy that fed into this legislative proposal (Article 9, see below).

THE CHANGES THE PROPOSAL WOULD BRING

The Commission's legislative proposal revises many RED II provisions. The main legal basis for the revised RED II is Article 194(2) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), which is dedicated to energy and gives the EU a specific mandate to adopt policies relating to the development of new and renewable forms of energy. Article 194 was also the legal basis for RED II. Article 114 (internal market) is added as the legal basis for the revision of RED II because the Commission proposal also amends Directive 98/70/EC on fuel quality, which is based on that Article.

The Commission has opted for an amending directive (rather than a full recast) because of the relatively short time that has lapsed since RED II was adopted (21 December 2018) and transposed by the Member States (deadline of 30 June 2021). According to the Commission, the current proposal to revise RED II is limited to what is necessary to meet the EU's new climate goals for 2030.

Below are some of the key changes that the Commission proposal makes to RED II.

Article 1 (Definitions) is modified to include several new definitions of RES technologies as well as some modifications to existing definitions, reflecting a broader understanding of RES technologies.

Article 3 (Binding overall Union target for 2030) is amended to set a new EU target of a minimum 40 % share of energy from RES in final consumption, and also introduces an obligation to phase out support for electricity production from biomass from 2026 (with limited exceptions). Other changes aim to minimise the risks of unnecessary market distortions resulting from RES support schemes, and prevent Member States from supporting the use of certain raw materials for energy production.

Article 7 (Calculation of the share of energy from renewable sources) is amended so that i) renewable fuels of non-biological origin (RFNBOs), mainly

hydrogen, are accounted for in the sector in which they are consumed (electricity, heating and cooling, transport), and ii) renewable electricity used to produce RFNBOs is not included when calculating the share of RES in that particular sector.

Article 9 (Joint projects between Member States) is amended to introduce an obligation on Member States to have a cross border pilot project within three years, and jointly define and cooperate on the amount of offshore renewable generation to be deployed within each sea basin by 2050.

Article 15 (Administrative procedures, regulations and codes) is amended to strengthen the existing provisions on renewable power purchase agreements.

A new article 15a (Mainstreaming renewable energy in buildings) sets an indicative EU target of a 49 % share of RES in the heating and cooling of buildings by 2030, reinforces existing measures and introduces new ones to promote the switch from fossil fuel heating systems to RES.

Article 19 (Guarantees of origin for energy from renewable sources) is amended to remove the ability of Member States not to issue guarantees of origin to a producer that receives financial support. This is closely related to changes to renewable power purchase agreements (see Article 15).

Article 20 (Access to and operation of the grids) is amended to enhance energy system integration between district heating and cooling (DHC) systems and other energy networks. A new Article 20a includes several provisions to facilitate system integration of renewable

electricity.

A new article 22a (Mainstreaming renewable energy in industry) sets an indicative target of increasing RES use in industry by +1.1 % per annum, together with a binding 50 % target for RFNBOs used as feedstock or as an energy carrier. It also introduces a requirement that the labelling of green industrial products must indicate the percentage of renewable energy used, following a common EU-wide methodology that has already been established.4

Article 23 (Mainstreaming renewable energy in heating and cooling) is amended so that the existing indicative target (+1.1 % annual increase) will become a binding baseline target. More generally, Member States will be obliged to carry out an assessment of their RES potential in this sector. The amended Article 23 will now propose a menu of measures to allow Member States to meet their heating and cooling targets, while at the same time ensuring vulnerable consumers have access to such financial support, as they would otherwise lack sufficient up-front capital.

Article 24 (District heating and cooling) is amended to increase the indicative target of RES from waste heat and cold in district heating and cooling (DHC) systems from +1 % to 2.1 % per annum. Third party access will be expanded for most DHC systems (>25 MWth) and a new definition of 'efficient DHC system' is introduced in line with related changes to the Energy Efficiency Directive.

Article 25 (Mainstreaming renewable energy in the transport sector) is amended to set a new 13 % greenhouse gas intensity reduction target; increase the sub-target for advanced biofuels (from 0.2 % in 2022 to 0.5 % in 2025 and 2.2 % in 2030); and introduce a new 2.6 % sub-target for RFNBOs. A credit mechanism is introduced to promote electromobility, under which economic operators that supply renewable electricity to electric vehicles via public charging stations will receive credits they can sell to fuel suppliers, who can use them in turn to satisfy their fuel supplier obligation.

Article 27 (Calculation rules with regard to the minimum shares of renewable energy in the transport sector) is amended to reflect the new targets above (see Article 25) and to remove the multipliers associated to certain renewable fuels and to renewable electricity used in transport under RED II.

Article 29 (Sustainability and greenhouse gas emissions saving criteria for biofuels, bioliquids and biomass fuels) is amended to extend the existing land criteria for agricultural biomass (e.g. no-go areas) to forest biomass (including primary, highly diverse forests and peatlands). The aim is to prohibit the sourcing of biomass for energy production from primary forests. No forest biomass for electricity-only installations will be eligible for RES support from 2026, with a ban on national financial incentives for using saw or veneer logs, stumps and roots for energy generation.

Article 29 also sets out how small-scale biomass-based heat and power installations (5MW+ total rated thermal capacity) will now be required to meet EU sustainability criteria that already apply to larger installations under RED II. Furthermore, minimum greenhouse gas saving thresholds for electricity, heating and cooling production from biomass fuels, which already exist in RED II but apply only to new installations, will henceforth also apply to existing installations.

A new article 29a (Greenhouse gas emissions saving criteria for renewable fuels of non-biological origin and recycled carbon fuels) would ensure that such fuels can only be counted towards the various targets set out in RED II if their GHG emissions savings are at least 70 %. This will encourage the development of 'green hydrogen' obtained from RES rather than fossil fuels.

A new article 31a (Union database) extends the scope of this EU database so that it can cover fuels not only in the transport sector, but also enable the tracing of liquid and gaseous renewable fuels and recycled carbon fuels as well as their life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions. This EU database already exists as a monitoring and reporting tool where fuel suppliers must enter the information necessary to verify their compliance with the fuel suppliers' obligation (set out in Article 25).

The Commission proposal sets 31 December 2024 as the anticipated date by which Member States must transpose the revised RED II into their national laws.

ADVISORY COMMITTEES

The European Economic and Social Committee (EESC) is preparing an opinion (TEN/748) on the revision of the Renewable Energy Directive. The joint rapporteurs are Christophe Quarez (Workers – France) and Lutz Ribbe (Diversity Europe – Germany). The plenary vote is provisionally scheduled for 8-9 December 2021.

The Committee of the Regions (CoR) is preparing a legislative opinion (CDR 4547/2021) on the revision of the Renewable Energy Directive. The rapporteur is Andries Gryffroy (EA, Belgium) and the opinion is scheduled for adoption in the 27-29 April 2022 plenary session.

NATIONAL PARLIAMENTS

The Commission's proposal was transmitted to national parliaments on 1 July 2021 and they had until 8 November 2021 to submit reasoned opinions, of which two were received. The Irish Parliament considered the 'Fit for 55' package as a whole and came to the view that the principle of subsidiarity was infringed, although no specific concerns were raised about the RED II proposal. The Swedish Parliament instead concluded that the RED II proposal specifically breached the principle of proportionality, since the level of detailed regulation proposed by the Commission, in particular regarding bioenergy, went beyond what is necessary to achieve the given objectives.

STAKEHOLDER VIEWS

The Commission's 'fit for 55 package' met with mixed reactions from stakeholders, with some praising it as an important milestone in tackling climate change, while others felt it lacked ambition for a task of this magnitude. Given the numerous legislative proposals, covering all aspects of climate and energy legislation, only certain stakeholders discussed the revised RED II in detail.

Environmental groups are generally critical of the 'fit for 55 package', including the revised RED II. Greenpeace argues that a renewable energy target of 40 % is too low to keep global temperature rises below 1.5°C, as confirmed in the energy scenario modelled by the Climate Action Network (CAN). CAN also made a rapid assessment of all the main fit for 55 files, and concluded that RED II needed a higher EU target of at least 50 %, to be supported by binding national targets. According to CAN, RED II should broaden incentives for system integration of renewable electricity; strengthen bioenergy criteria; and close the door to fossil fuels for hydrogen production. The European Environmental Bureau argues that the Commission has missed a historic opportunity to phase out fossil fuels from the energy system, and a minimum RES target of 50 % by 2030 is necessary to deliver on EU and global decarbonisation objectives.

WWF also fully supports this 50 % target. Fern meanwhile is very critical about continued EU support for forest biomass, insisting that the new provisions of RED II to protect forests are inadequate and not additional to existing proposals. In the absence of stronger protections, Fern argues that the higher RES targets in RED II will encourage coal-fired power plants to switch to biomass, thereby further increasing the destruction of forests.

Industry responses tend to be more positive, especially those of most renewable producers. Wind Europe strongly supports the 40 % RES target for providing certainty for businesses and consumers, and calculates that 'the EU will need 451 GW of wind power capacity by 2030, up from 180 GW today... a major acceleration in the expansion of wind energy'. According to Wind Europe, the revised RED II would 'help the development of offshore wind including hybrid offshore wind farms that have multiple grid connections', and improve the legal framework for corporate power purchase agreements (CPPAs). Solar Power Europe believes the Fit for 55 package 'represents a landmark moment for the European energy transition and the solar industry in particular'. They welcome the provisions on CPPAs and improvements to the guarantees of origin framework, the strong support for green hydrogen (including targets), and efforts to accelerate the permit granting process. However, they maintain that a 45% RES target is necessary to achieve the EU's decarbonisation goals. Renewable and low carbon liquid fuels platform believes the revised RED II 'provides the opportunity to step up the contribution of sustainable and renewable liquid fuels in transport' and supports a 'technology-neutral approach, enabling the use of best available options with proven emissions-reduction credentials'. Hydrogen Europe welcomes targets for the use of renewable hydrogen in industry and transport, as well as the introduction of a level playing field for RES by removing multipliers associated with certain renewable fuels. In contrast, Bioenergy Europe criticises the Commission for choosing to reassess sustainability criteria at a time when the transposition of RED II still needs to be completed by most Member States. They call for a science-and practice-based assessment, and the avoidance of abrupt rule changes that create legal uncertainty. Most critically, Bioenergy Europe maintain that the proposed framework for forest biomass is improper. Eurofuel (heating oil association) has published a position paper on review of RED II (February 2021) that welcomes and supports the goals of this reform but also calls for the EU to adopt a more innovation-friendly approach that can adjust easily to future technological changes.

LEGISLATIVE PROCESS

The file has been referred to the European Parliament's Committee for Industry, Research and Energy (ITRE), which appointed Markus Pieper (EPP, Germany) as rapporteur, who will produce a draft report. The Committee for

Environment, Public Health and Food Safety (ENVI) will be associated to this report under Article 57, and has

appointed Nils Torvalds (Renew, Finland) as its rapporteur. The Committees for Regional Development

(REGI), Transport and Tourism (TRAN), Agriculture and Rural Development (AGRI) will provide opinions.

The Commission presented its RED II legislative proposal in a session of the ITRE committee on 14 October 2021 and a discussion followed.

This file has been discussed at working party level in the Council of Ministers, and was one of the main topics of discussion at the informal meeting of energy ministers held on 22 September 2021.

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT SUPPORTING ANALYSIS

Zygierewicz A. with Salvador Sanz L., Renewable Energy Directive, EPRS, European Parliament, March 2021

OTHER SOURCES

Renewable Energy Directive, 'Fit for 55 package', Legislative Observatory (OEIL), European Parliament.

ENDNOTES

1 EPRS published legislation-in-progress briefings on RED II (January 2019) and the Governance of the Energy Union regulation (January 2019) that provide more detail and context about these reforms and their process of negotiation.

2 The Commission's renewable energy progress report (October 2020) contains data up until the year 2018, when the United Kingdom (UK) was still an EU Member State. The RES shares listed in the Commission's report therefore include energy consumption from the UK, unless specifically indicated otherwise as EU-27.

3 Technical assistance studies have been published on the following topics: Technical support for RES policy development and implementation (September 2021); assessing options to establish an EU-wide green label with a view to promote the use of renewable energy coming from new installations (July 2021); preparation of guidance for the implementation of the new bioenergy sustainability criteria (April 2021); realisation of the fourth report on progress of renewable energy in the EU (April 2019); and realisation of the 2018 report on biofuels sustainability (April 2019).

Policy studies have been published on job creation and sustainable growth related to renewables (February 2021); shaping a sustainable industry: guidance for best practice and policy recommendations (April 2020); and competitiveness of the renewable energy sector (August 2019), as well as a scoping study on setting technical requirements and options for a Union database for tracing liquid and gaseous transport fuels (September 2020).

4 This methodology is set out in Recommendation 2013/179/EU.

5 This section aims to provide a flavour of the debate and is not intended to be an exhaustive account of all different views on the proposal. Additional information can be found in related publications listed under 'European Parliament supporting analysis'.

CONTACTS

E. eprs@ep.europa.eu (contact)

www.eprs.ep.parl.union.eu (intranet)

www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank (internet)

http://epthinktank.eu (blog)

LATEST RESEARCH REVIEW - BRUSSELS MARCH 2022

The European Climate, Infrastructure and Environment Executive Agency (CINEA) together with the Directorate-General for Research and Innovation (DG RTD) and the STEERER project (Structuring Towards

Zero Emission Waterborne

Transport) are organising the workshop “Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation delivering smart, green, safe and competitive waterborne transport”, which will take place on 7 February in Brussels (Residence Palace, Rue de la Loi 155) as well as online.

Horizon

Europe

The workshop will present the results of seven years of investments in research and innovation towards smart, green and integrated waterborne transport, which took place in the framework of Horizon 2020. The event will also provide an outlook to the future in the light of the new

Horizon Europe programme.

THE

DRIVERS: LEGALLY BINDING TARGETS ?

There are as yet not legally binding targets coming out of events such as COP26 (for example)

- hence

where some players may say they are agreeable to such targets, in reality

they can sit on the fence as observers with fingers crossed, hoping that other countries

will produce the technological miracles to carry their expansion plans forward,

and dig them out of their fossil fueled holes. Development such as that funded by

waterborne and ZEWT

programmes shows good faith intentions from the EU, and solid advances in

knowledge, even though somewhat plodding along, it is still progress.

EMISSIONS

At COP26

it was agreed countries will meet next year to pledge further cuts to emissions of

carbon dioxide (CO2) - a greenhouse gas which causes

climate

change.

This is to try to keep temperature rises within 1.5C - which scientists say is required to prevent a "climate catastrophe". Current pledges, if met, will only limit

global warming to about

2.4C, and even those are slipping. Without stepping

up change, to get the job done, the human race and the planet are in for a

rough ride.

COP26 was the

event in Glasgow where countries revisited the climate pledges they made under the

2015 Paris

Agreement. COP27 is to be held in Egypt.

FOSSIL FUEL SUBSIDIES

World leaders agreed to phase-out subsidies that artificially lower the price of

coal, oil, or natural gas.

However, as with other so-called commitments, no firm dates have been set.

These subsidies are braking the adoption of renewables, making solar, wind

and hydrogen power appear less competitive than they actually are. Indeed,

renewable electricity

is cheaper than coal

burning and nuclear

power stations.

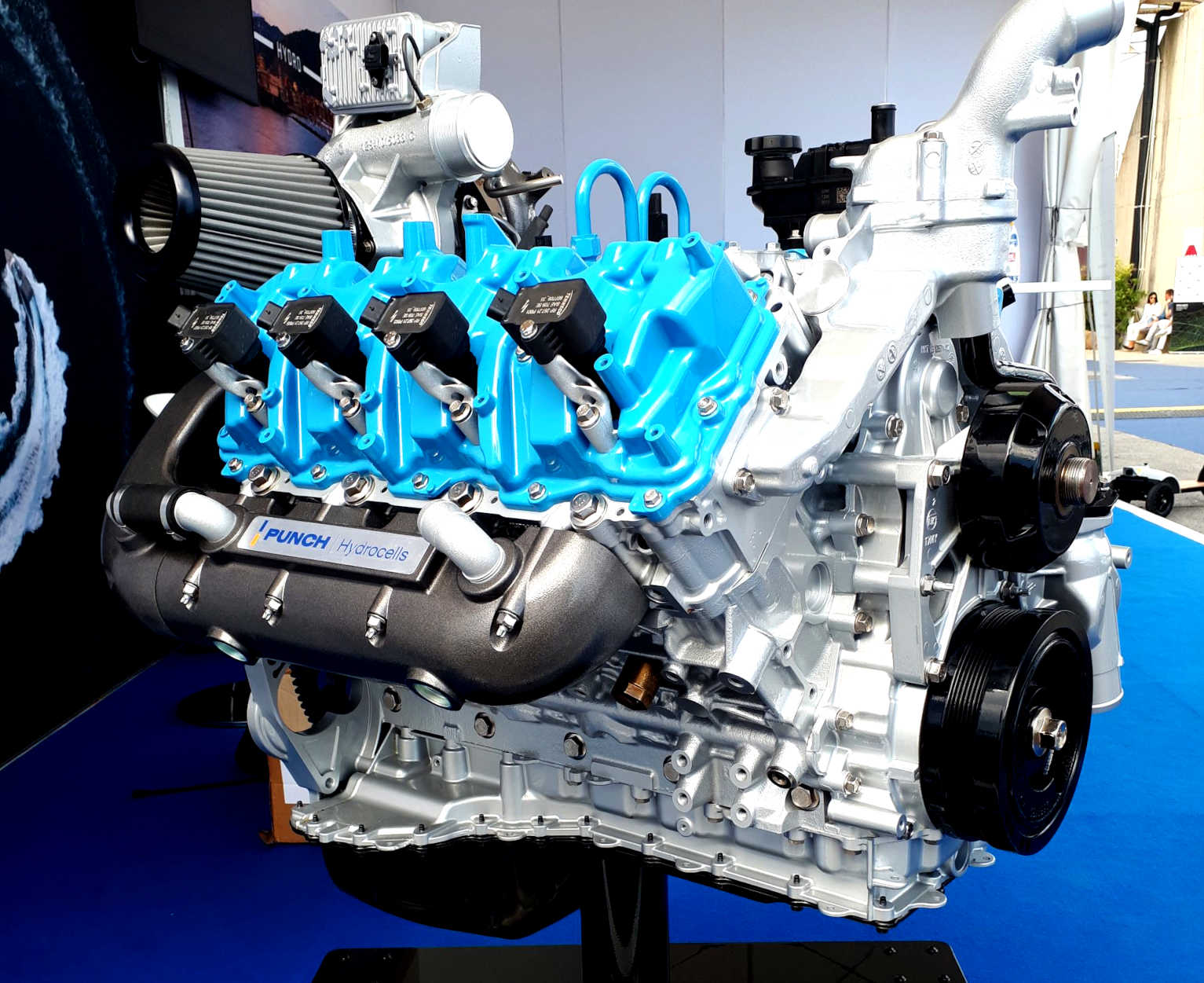

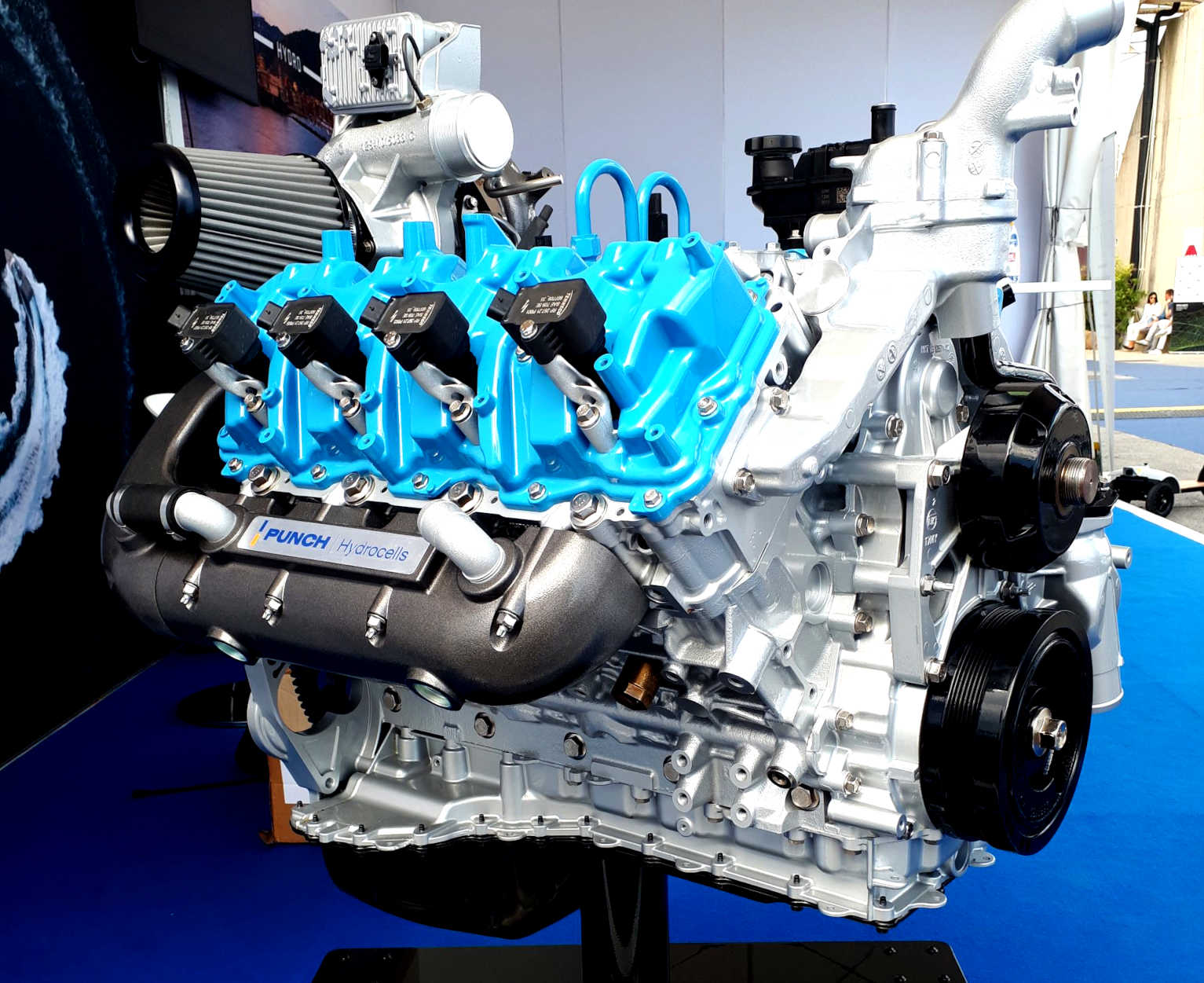

DURAMAX

- Hydrogen fueled diesel engines such as the 6.6 liter unit above, retain

the familiar ICE format and service life limitations with the advantage that ship

operators understand the technology.

FUNDING DEVELOPMENT

Financial organisations controlling $130tn agreed to back "clean" technology, such as

renewable

energy, and direct finance away from

fossil fuel-burning industries.

The initiative is an attempt to involve all of us to meeting net zero targets.

The

European Union (EU) funds a number of research and innovation projects from

a pool of money, that is designed to accelerate technology by way of a green

driver aimed at economic stability. The policies and thus, calls for

proposals are looking for near-to and long-term projects to assist with the

transition to zero emission transport, that is sustainable. Hence Net Zero.

Technology

Readiness Levels are thus all important. With a tendency to leap over

development hurdles, as though the technology is more advanced than it

actually is. Leaving holes in our knowledge bank.

Typically,

pure research is 100% funded. Levels of funding then fall significantly, on

the presumption that industry will make up the shortfall - even where

conflicts of interest exist - to block development that threatens existing

products and fuels.

When weighing up future-fuel options, it is becoming increasingly necessary to take a well-to-wake approach to calculating GHG emissions. The European Commission recently adopted the ambitious Fit for 55 Package, a set of proposals aimed at making the EU’s climate, energy, land use, transport and taxation policies fit for reducing net emissions by at least 55% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels. This package places even greater demands on the maritime industry, which is expected to reduce its emissions by 75% by 2050 compared to 2020 levels.

SIGNS

FROM ABOVE - JULY 2021 - Floods

in London, Belgium and Germany cause huge damage to property, with temperatures

soaring. Despite this, one crisis now circulating is the “global water crisis”. That, in combination with the global warming crisis, of course is leading to mass crop failures, thirst and later mass starvation, unless we act

now.

|